Everyone has heard of de-extinction. Everyone. If they haven’t, and are brave enough to ask casually in conversation, and if the person responding doesn’t want to take the time to actually explain it—or doesn’t actually know—then the response will consist of exactly four words: It’s basically Jurassic Park.

As a result, the story is everywhere. While some of my no less-obscure Google Alerts lie dormant for weeks before cropping up with new material from some weird corner of the internet, de-extinction merits a several-times-weekly type discussion. Everyone—from Think Christian to the Martha’s Vineyard Gazette—is interested in the fact that this could really be happening. Jurassic Park could really be happening.

But is it? Yes and no. What has been framed within the Biblical rhetoric of revival and resurrection is really occurring using the now commonplace approaches of genetic engineering, amped up to a level that—while undoubtedly impressive—raises many more questions about what we can and should do with a technology that’s already steeped in ambivalence.

“This is not about making the perfect wooly mammoth—it’s about making cold-resistant elephants,” said Harvard geneticist George Church at a conference in October. Church’s lab is currently working to revive a wooly mammoth-like elephant in hopes of restoring the grasslands of the Arctic tundra. Or, as he told New York Times Magazine in response to criticism regarding the project’s hype from fellow researchers, “I would like to have an elephant that likes the cold weather. Whether you call it a ‘mammoth’ or not, I don’t care.” (The NYT Mag article in question ran with the headline “The Mammoth Cometh.”)

Techno-scientifically, engineering an elephant that is fat, hairy, and has cold-adapted hemoglobin would be an impressive feat requiring “a few dozen” changes to the animal’s genome. But resurrection, this is not.

So why is it called de-extinction in the first place? The story goes back to Stewart Brand, a man who has done more to define our day-to-day experience in the digital age than most people who actively played a part in creating it. To put it simply, the 75-year old Brand loves playing with big ideas, and the idea of bringing back extinct species is nothing if not huge.

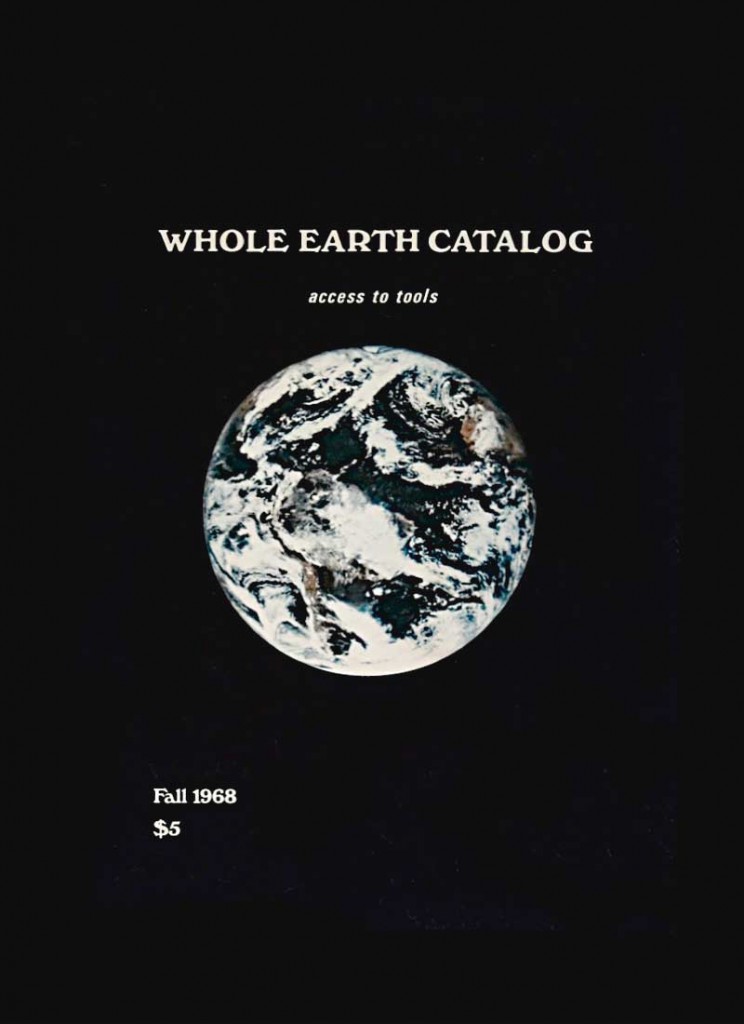

The Whole Earth Catalog has maybe one of the best origin tales, a relic as well-worn as the yellowing, wrinkled copies now propped up on used bookstores shelves across the United States.

Brand graduated from Stanford with a degree in ecology in 1960 before completing a short stint in the army and returning to San Francisco in the midst of its countercultural upheaval. In 1966, he began a public campaign to have NASA release a photograph of the whole Earth taken from space. Brand argued that seeing the planet in its entirety could be a powerful symbol to galvanize environmental stewardship from all who occupied “Spaceship Earth,” a term popularized to emphasize the vulnerable nature of our tiny vessel’s resources. In 1967, NASA took that photo. And in 1968, Brand founded what became one of the defining publications of the American counterculture, featuring the NASA-released photo and the words “WHOLE EARTH CATALOG / access to tools” on its stark black cover. Small-scale tools, Brand argued, were the keys to personal empowerment.

Over the next four years, the Catalog would come to sell over 2.5 million copies. While on one level it functioned as a purveyor of small-scale technologies to the hundreds of thousands of young commune dwellers scattered across the US, it also served as a point of communication for other communities that Brand, a seamless networker, moved fluidly between: most notably, the experimental art scenes in New York and San Francisco, the Bay Area psychedelic community, and the world of industry-based science and technology.

As such, the Catalog contained such seemingly incongruous items as buckskin jackets, Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic domes, solar collectors, and wood stoves, as well as a $4900 Hewlett-Packard desktop calculator, subscriptions to magazines like Scientific American, and books on ecology and cybernetics. To contemporary readers of the Whole Earth Catalog, its first line, “We are as gods and might as well get good at it,” rang the clarion call of a new sort of technological embrace.

“When these groups met in its pages, the Catalog became the single most visible publication in which the technological and intellectual output of industry and high science met the Eastern religion, acid mysticism, and communal social theory of the back-to-the-land movement,” writes media theorist Fred Turner. Historian Andrew Kirk further argues that this iconoclastic forging of communities represented a “new alchemy” of environmentalism that emerged in the 1970s, where environmentally conscious consumption began to count as environmental awareness—or even activism—with technology serving as its main conduit.

In April 2013, over four decades after the final issue of the Whole Earth Catalog was published, a Berlin-based art group put together an exhibition entitled, “The Whole Earth: California and the Disappearance of the Outside,” part of an ongoing series called “The Anthropocene Project.” The catalog’s stark white cover featured the image of the moon in the foreground, the earth tiny and vulnerable in the distance, with a large shadowed hand extending down towards it—either reaching out as peace offering, as acknowledgement, or threatening to scoop it up for its own use. The exhibit dealt with “the transgression of boundaries and the emerging consciousness of limits in the sign of the ‘one earth,’” the curators wrote. “The Whole Earth Catalog…played a key role in mediating and popularizing images of the ‘earth system.’ The vision of the global Internet and central concepts of the ecology movement can trace their roots back to this moment.”

In February of 2013, Brand gave an eighteen-minute TED Talk entitled, “The dawn of de-extinction. Are you ready?” In the talk, which has since been viewed over 1.6 million times and has been translated into 24 languages, Brand told a tale in broad strokes of the wildlife-destroying Anthropocene, as evidenced by the extinction of the once ubiquitous passenger pigeon.

“Sorrow, anger, mourning. Don’t mourn—organize,” Brand told an audience of people who had each paid several thousand dollars to attend the popular talk forum devoted to spreading the “power of ideas.” “What if you could find out that, using the DNA in museum specimens, fossils maybe up to 200,000 years old could be used to bring species back?” Brand asked. Thanks to new developments in genome assembly, synthetic biology, and interspecies cloning, Brand said, bringing extinct species back into existence was now a distinct possibility.

This moment effectively served as the launching pad for Brand’s newest venture, an organization called Revive & Restore that would be devoted to resurrecting extinct species using biotechnology. The project would be just one arm of Brand’s Long Now Foundation, a non-profit dedicated to getting “people thinking past the mental barrier of an ever-shortening future.” Perhaps most well known for its 300-foot-tall stainless steel 10,000 Year Clock—financed by a $42 million investment from Amazon.com founder Jeff Bezos and built inside a mountain that Bezos owns in Texas—Long Now’s most recent project was sending a nickel disk inscribed with 1,500 languages to “Rosetta’s Comet” via the Rosetta space probe. While these projects are at turns overly glorified or dismissed as New Age oddities, they are foremost large-scale art projects. Viewed in this way, the de-extinction project is the perfect addition to Brand’s portfolio.

While Revive & Restore’s flagship project is to clone the passenger pigeon back into existence, it is also aiming to resurrect the wooly mammoth in collaboration with Church’s lab at Harvard. In addition, it plans to serve as a de-extinction hub of sorts, convening meetings and fostering communication across disciplinary boundaries among the scientists, conservationists, and ethicists working on relevant aspects of the project worldwide.

However, the project also has another, bigger goal: Brand wants to persuade the environmentalist and conservationist communities, which he repeatedly argues are stuck in a negative view of the world, to instead embrace the optimism of technology. “The environmental and conservation movements have mired themselves in a tragic view of life,” Brand wrote in a letter to Church and biologist E.O. Wilson before launching the project. “The return of the passenger pigeon could shake them out of it—and invite them to embrace prudent biotechnology as a Green tool instead of menace in this century.”

“Could be fun. Could improve things. It could, as they say, advance the story,” he wrote.

A year later, however, the story has mostly raised lots of questions from disparate stakeholders staring at eachother across a vast expanse of muddled misunderstanding.

How arbitrary or specific are species boundaries in the first place?

In an era when endangered species are being cloned in zoos, where are conservation’s limits?

What role have/do/should humans play in reinventing nature?

These questions are the beauty of a project whose grandiose packaging far outweighs its realities: Revive & Restore currently has only one full-time employee, a passenger pigeon-enthusiast with a bachelors degree in ecology but no advanced scientific qualifications. He has admitted it could be up to two decades before anything closely resembling a flock of passenger pigeons takes to the skies. Yet it’s advancing a story.

In one of the few bioethical analyses of de-extinction written to date, author Ronald Sandler concluded by saying that, “The considerations in favor of de-extinction are largely techno-science oriented, not conservation-oriented.” Given that there is no pressing need to pursue it, from Sandler’s ethical perspective, “De-extinction is a luxury.”

It may partially be an exercise in seeing what we can do with the latest genome editing technologies, whether we can make a creature as large an elephant give birth to something slightly different, whether we can then teach those animals to live and breed together, whether they can then manage to do so in the Arctic, and whether then some of the damage wrought as a result of climate change might somehow be erased via the pounding feet of herds of fat, hairy elephants. If so, it’s a bad scientific solution; but in the meantime, it’s a great story.

By the early 1970s, with thousands abandoning the rural communes they once fled cities to build, the New Communalist vision was fading fast. So too were Brand’s former ideals about routes to self-sufficiency. Instead, in the decade after he published the Last Whole Earth Catalog in 1971, Brand shifted the utopian rhetoric of personal empowerment he and others had previously placed on rural commune dwelling to a new focus: digital technology. According to Turner, this shift “helped redefine the microcomputer as a ‘personal’ machine, computer communication networks as ‘virtual communities,’ and cyberspace itself as the digital equivalent of the western landscape into which so many communards set forth in the late 1960s: the ‘electronic frontier.’”

Will de-extinction ever become a reality? Who knows, but it’s not looking likely. Instead, like the New Communalists’ visions of small-scale utopias contained within the Whole Earth Catalog, it’s probably going to remain only as a relic of a greater shift. Looking back, its main quality as a story may be that it perfectly embodied the contemporary conversation on the power of biotechnology—overblown in both its hopes and its anxieties. We’re reinventing nature, dudes. Because, Jurassic Park.