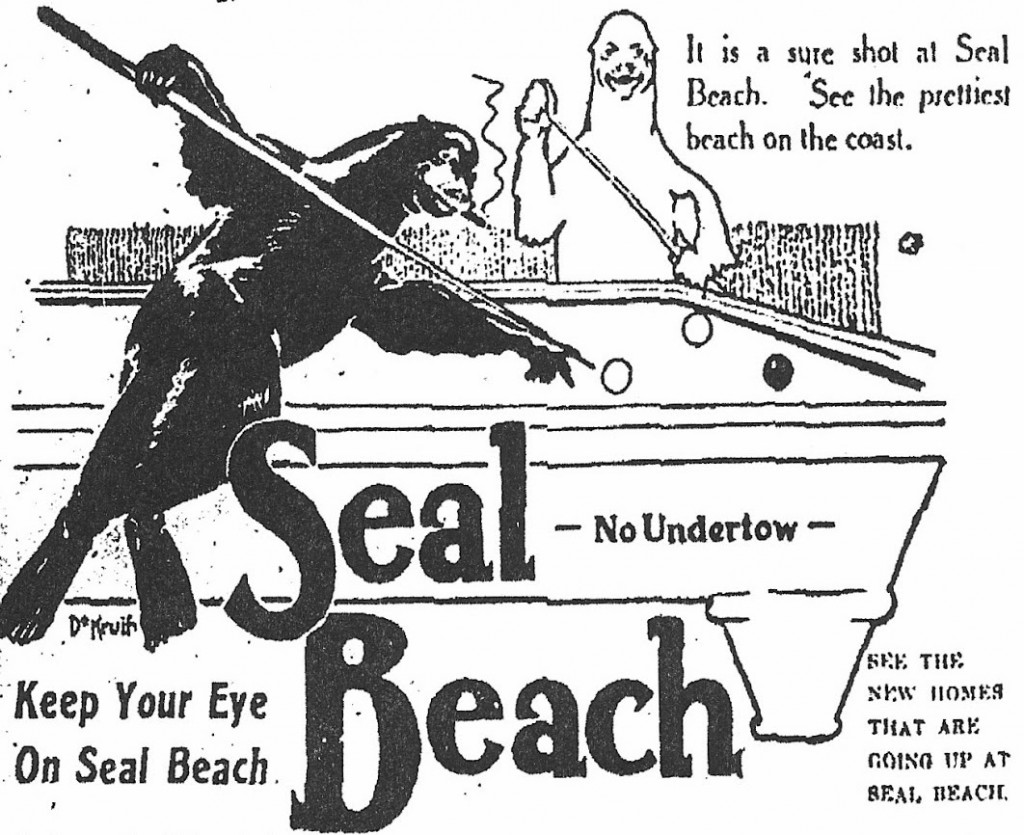

Many visitors to Seal Beach, California think it gets its name from the 5000-acre Navy depot that employs so many of its residents. But they’re wrong; it’s named for the animal that once colonized the sandspits near the beach. In the 1900s, during Seal Beach’s short life as a resort town, vacation-goers could stand on the pier and watch thousands of the glistening mammals flop and moan, wriggle in and out of the water, out of the deep of the sea and onto the spit. Town boosters spread word of Seal Beach using imagery of the animals: seals dancing with a ball perched on the nose, seals serving up a gourmet lunch, seals cranking back in their office chairs, smoking cigars, the riches of their profitable appeal. Come to Seal Beach, they said, watch us at arm’s length, as a destination scintillates before you: plinking music, a casino, a rollercoaster from the San Francisco World’s Fair.

But two wars and the Depression quickly revised the Seal Beach fantasy. The pier disappeared, the Navy depot was built, and offshore drilling began in the mid-1940s. Sometime around then the seals checked out, leaving a town with a misled sense of identity and, perhaps, relationship to its wildlife. For this is the same place, just south of Los Angeles County, that passed an ordinance last month to exterminate all of its coyotes.

Coyotes’ attacks on Seal Beach pets seem to be increasing. The “seem to be” is deliberate: It’s not clear whether the coyotes’ encounters with domesticated animals are in fact growing, and local authorities have admitted the difficulty of ascertaining firm numbers on either count. But what’s certain is that as coyotes populate unremittingly across the U.S., and in Seal Beach, there’s been a recent echo effect in anguished reports of coyote encounters. Seal Beach residents are gathering in front yards and stringing photographs of canine victims to the predators to branches, like so many tear-jerking Christmas trees. They are organizing Facebook groups called “Coyote Watch,” and “The coyotes are a problem for Seal Beach.” They are calling community meetings to air stories of their traumatic encounters, like: A man who came home from a daughter’s school play to find the pincers attacked and dying in the backyard. A woman who carries precautionary mace, a whistle, and a headlamp on dog walks around the neighborhood. Another who has seen a coyote regularly enough at her doorstep that she has named it “Joe” (normally naming an animal is a sign of affection, but apparently not in this case). “I don’t want to co-exist with the coyote here in Seal Beach,” one man told the Seal Beach City Council last August. “I want my daughters…and my wife to walk the dog through the neighborhood and feel safe—and we don’t.”

Fears crescendoed at that City Council meeting, and in September, councilmembers agreed unanimously that the solution to the coyote problem was to trap and gas the animals with carbon dioxide. It’s a decision that’s been met with considerable media attention in the state; few trapping programs still exist in California since historically, trapping has backfired. Research shows that weaker coyotes tend to be those that fall prey, leaving the larger and more intelligent to mate and even increase a population. And in California animal shelters, gassing is an illegal method of euthanization. Activists have protested Seal Beach’s plans as inhumane, organizing their own protests in support of more “integrated” measures to protect pets and humans alike: coyote ‘hazing’ (in an encounter with a coyote, create noise and try to appear as large as possible), keeping trash cans locked up and food inside, walking pets in daylight hours, and never leaving them alone in the yard.

Traumatized pro-trappers would probably argue that these measures don’t do enough to address coyotes’ brazen nature, and on one level they’re probably right. It’s entirely possible that a coyote might visit your yard while you’re waving your arms and yelping in it, or that you’d encounter one on a morning jog, or that one might come not in search of your trash, but for innocuous fallen citrus from the trees in your yard.

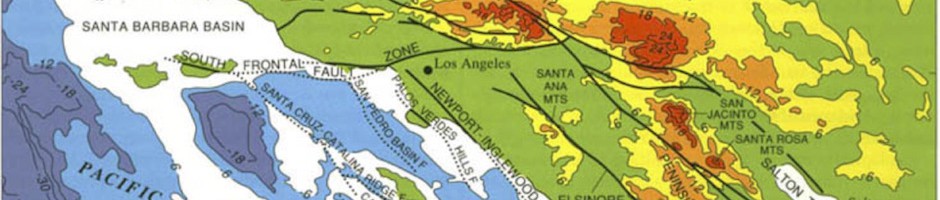

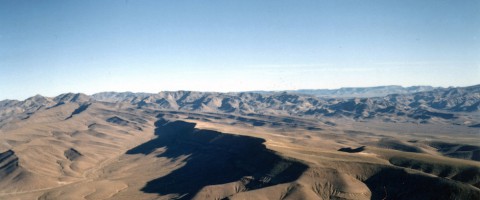

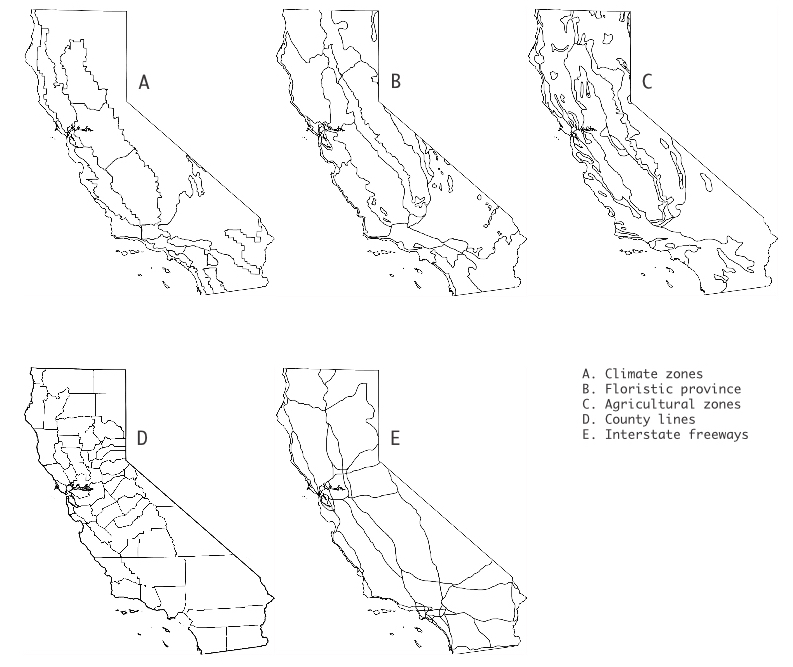

But Seal Beach residents may also suffer a chronic misunderstanding of the place they live. Southern California is a region defined by what biologists term the ‘ecotone’: a transition zone between ecological communities “whose boundaries may be relatively abrupt (as between chaparral and lawns) or gradual (as between domestic, feral, and wild animals).” That’s Mike Davis writing in Ecology of Fear, a book that argues how the evolution of urban Southern California—more than any other citified region in the U.S.—cannot be understood apart from its precarious seat in nature. From its earthquakes, its seasonal fires, the drought that is the status quo, the defining edge of mountain and desert, it’s a place whose basic contract rests on the interplay of ‘urban’ and ‘wild.’

Coyotes are the tricksters of the Southern California ecotone; they pass cunningly across borders that are fuzzy to begin with, shifting shapes depending on conditions. Some hunt in packs, others individually. Some sleep at night, others are nocturnal. Take away one kind of food source, and coyotes will find another. Coyotes will eat fresh prey if they have the option—like squirrels, rabbits, mice, and sometimes deer—but they’ll also eat berries and roots, human trash, fallen fruit, pet food, and pets, if they are desperate. (Some have attributed the apparent rise in coyote predation on small dogs and cats to diminished food supplies as a result of the West’s historic drought).

It’s no surprise that coyotes figure prominently in Native American literature, which at turns praises and admonishes the canine for its interminable curiosity and refusal to abide by the rules of any one animal or any one world. In this canon, the insatiable, brazen coyote regularly takes advantage of its knowledge of other beings, satisfying its hunger by manipulating the hunger of others.

Coyote was going along by a big river when he got very hungry. He built a trap of poplar poles and willow branches and set it in the water. “Salmon!” he called out. “Come into this trap.” Soon a big salmon came along and swam into the chute of the trap and then flopped himself out on the bank where Coyote clubbed him to death. “I will find a nice place in the shade and broil this up,” thought Coyote.

In his catalogue of rule-breakers mythical and real, Trickster Makes This World, Lewis Hyde writes of how the mythical Coyote takes advantage of his prey’s instincts to capture them. In this case, a Nez Pierce tale, the salmon that swims upstream to spawn leaps into Coyote’s trap out of natural hunger: “The worm just sits there; the fish catches itself.” In another story from the Crow, Coyote traps two buffalo by coercing them to stampede towards the sun—where they can’t see where they are going—then over a cliff.

In 1915, Seal Beach took on the name and image of a pinniped to shape its sense of place. Maybe that fast failure at animal control is somewhere at the root of the new coyote ‘problem’: a plain misunderstanding of place. Trap the coyotes, gas the coyotes, and they will come back. They will come back in stronger numbers, smarter, and maybe even keener to play the instincts of the humans they rely on to survive.