In late 1905, two biologists from Clark University — Oris Polk Dellinger and David Gibbs — worked in a continuous relay for six days and five nights to observe several Amoeba proteus in their “daily lives.” Recording their hourly movements, Dellinger and Gibbs tried to discern whether the amoeba’s life patterns fell into the rhythmic ebbs and flows of work and rest — tied to the search and attainment of food — that were the basis for all known animal life. Observed under a microscope, diagrammed in their zig-zagging movements, and photographed landing their prey, the biologists found that the amoeba too exhibited these characteristic patterns. Viewed in the context of their behaviors, Dellinger and Gibbs concluded, the amoeba must be considered a rightful member of the animal kingdom. Much anthropomorphizing ensued. The following quotes and images can serve as a summary of their 1908 paper, “The Daily Life of Amoeba Proteus“:

INTRO: AMOEBAS ARE EXISTENTIALLY IMPORTANT

“The question of the behavior of amoeba is not a new one. The movements of no one animal have been studied so repeatedly, so carefully, for so many years, and so frequently referred to as those of the amoeba…The amoeba figures in discussions of immortality, heredity, and death.”

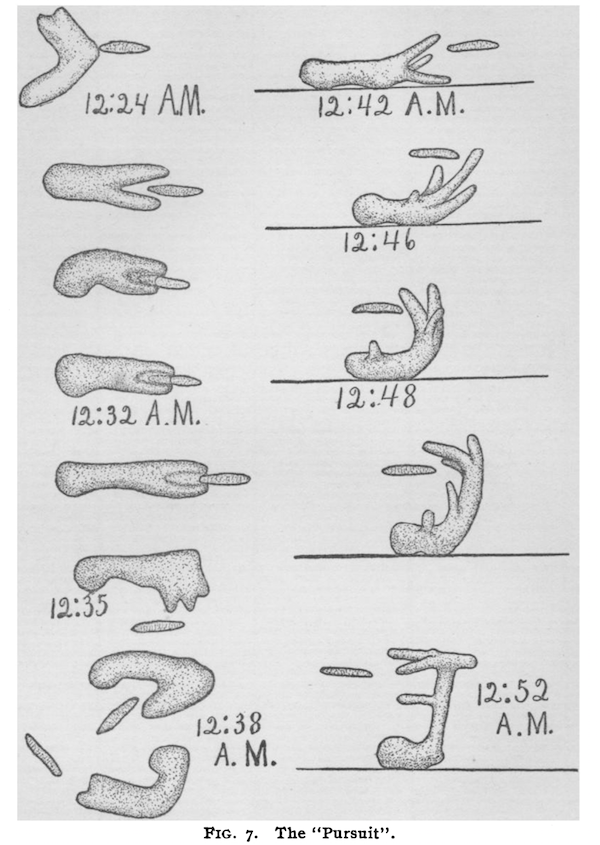

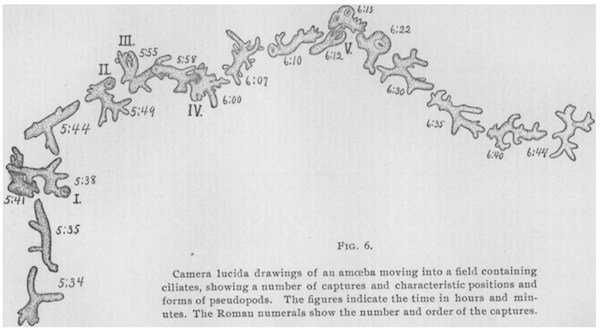

STEP 1: PURSUIT

“The amoeba often follows a paramoecium or a ciliate until it is caught or lost. This ‘pursuit’ may continue for twenty minutes or more as is indicated by the drawings of an actual instance, Fig. 7. When in ‘pursuit’ in this way the amoeba does not generally respond to other stimuli, especially if close upon its prey.”

STEP 2: CONFUSION

“An amoeba suddenly placed in the midst of a large number of paramoecia, which bump it and knock it about, usually makes no response to the separate stimuli, but seems ‘confused.’ Later, some amoebas in these circumstances, put out pseudopods and may ‘pursue’ a single paramoecium without much regard to touches from the others; while some appear never to get their equilibrium, but move off or take the spherical form.”

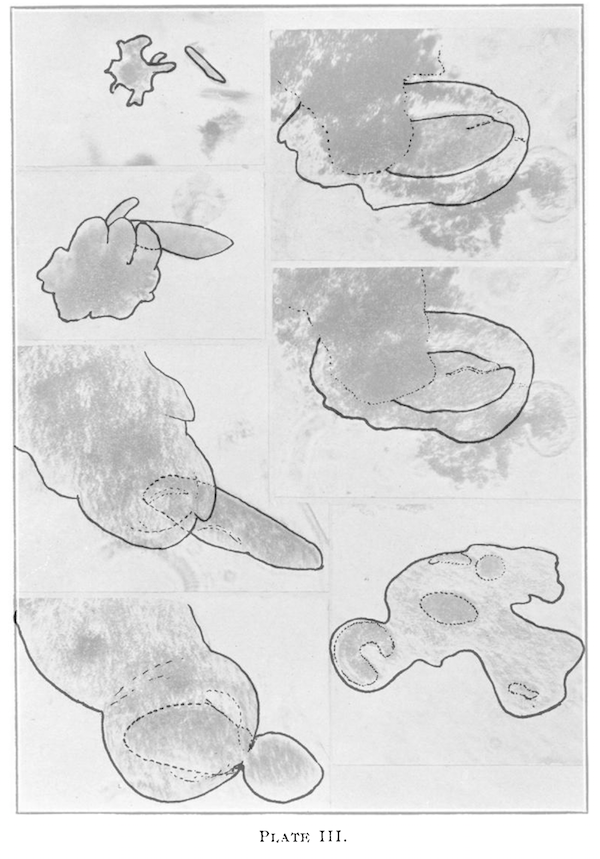

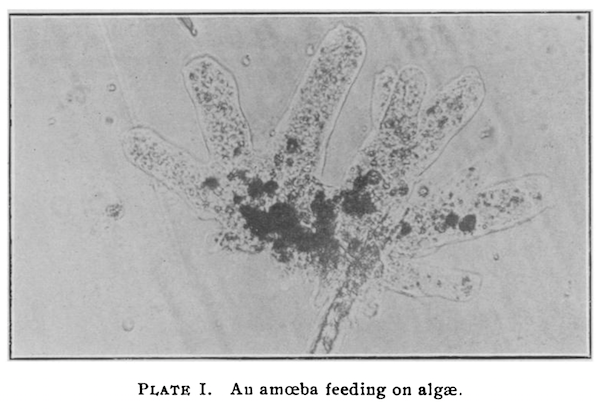

STEP 3: CAPTURE + FEEDING

“The intensely interesting sight of an amoeba after numerous trials gradually sliding its pseudopods around a feeding paramoecium, throwing a cover over it, closing the pseudopods, and gradually squeezing the struggling victim down to a rounded mass can hardly be described without using anthropomorphic terms. It requires a number of adaptations and considerable skill, which our observations seem to indicate are acquired by the ‘method of trial and error.'”

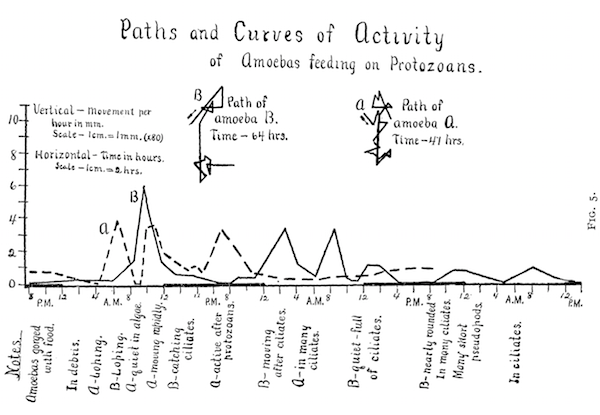

STEP 4: REST…BEFORE STARTING ALL OVER AGAIN

“Activity, feeding, rest; activity, feeding, rest…Activity, or the performing of work, requires energy which the protoplasm must supply. The period of rest appears to be simply the result of organic satisfaction, or a period of recuperation. It suggests the lowest form of sleep; for this tendency to rest, to sleep, as a food reaction is illustrated by the higher animals. In this respect this lowest form of life does not differ essentially from the higher forms.”

CONCLUSION: AMOEBA LIVES MATTER

“The study seems to show that amoeba can no longer be considered as a bit of but slightly differentiated protoplasm, but must take its place in the true animal series with the rudiments at least of true animal behavior.”

*Thanks to UCSF bioinformatics graduate student Patrick Harrigan for telling Method about this paper.