If one described the computer as one of the most important technologies of the 20th century, it would be tough to disagree. But when we talk about the computer, what exactly are we talking about? Is it the hardware? What about the software, the people who wrote it, or the industry for which software was written? What is different about the history of computers, and the history of electronics more generally?

To Michael Sean Mahoney, a historian of computers, the computer was a model for the difficult practice of history, an example of the problems of defining the scope of research, and the limits of definitions. To talk about the “inventor” of a technology — or an epochal definition like the “computer revolution” — is automatically to interact with a preconceived model of history. “‘[R]evolution’ is an essentially historical concept,” Mahoney wrote in Histories of Computing. “Even when turning things on their head, one can only define what is new by what is old, and innovation, however imaginative, can only proceed from what exists.”

We define the new via the old by reaching across different historical contexts, and finding similarities between different things in different times. Consider comparisons between computers and the Model T during the birth of PCs in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Here’s Mahoney again:

Apple, Atari, and others have boasted of creating the Model T of microcomputers, clearly intending to convey the image of a car in every garage, an automobile that everyone could drive, a machine that reshaped American life. The software engineers who invoke the image of mass production have it inseparably linked in their minds to the automobile and its interchangeable variations on a standard theme.

Using the Model T to invoke the idea that “this technology will become ubiquitous” is hardly original. Just ten years after the namesake device’s invention, Henry Ford himself boasted that the Ford Trimotor aircraft would do for the air what his Model T did for the roads. Of course, the Trimotor failed to have such iconic success, due to obvious differences between the aircraft and automobile markets. Simply to have Ford apply his manufacturing procedures to an aircraft would not be enough to duplicate the success of the automobile, which succeeded as much because of construction materials, financial markets, urbanization, and demographics as it did because of anything attributable to Ford himself. The historical contexts are different. A would not be to B as C was to D, because historical context is rarely transitive.

Today, analogies between technological devices and the Model T are repeated to the point of cliché. With a simple Google search, one can find “the Model T of” aircraft, bicycles, hoverboards, electric cars, driverless cars, payment systems, drones (two different options), satellite launchers, and even the biological mechanics of sharks. The Model T comparison has ceased to be a symbolic definition, and has instead become what’s been dubbed a snowclone: the act of comparison itself, repeated until it is noise rather than signal. Bereft of context, the snowclone becomes an idea echo chamber, repeating the sound of the idea until the idea itself is mostly unintelligible.

The snowclone gets its name from a 2004 discussion on the University of Pennsylvania’s Language Log, originally utilized to describe the lazy and clichéd journalistic practice of repeating some version of: “If Eskimos have N words for snow, X surely have Y words for Z.” Other examples are riffs on the Alien film poster tagline “In space, no one can hear you X,” or the ubiquitous “X is the new Y.” Snowclones are verbal memes, ideas that are formulaic, ultimately repeatable, and meaningful only in the context of that repetition. Even doge, perhaps the ne plus ultra of memes, qualifies as a snowclone. “So X, very Y.”

There does seem to be something meme-like about the evolution of historical technology analogies into stock phrases. Companies deploy memes for branding purposes all too often these days. There doesn’t have to be a carefully considered historical comparison; if you want to sell something to a market segment that has already accepted a particular product, labeling your new product as analogous to that older product is a foot in the door. The familiarity of the meme and of the referenced product makes it repeatable ad infinitum, a cookie cutter to shape new products. Today, the iPhone snowclone is almost as ubiquitous as iPhones themselves. “The iPhone of X” works if you want to appeal to iPhone owners, or if you want to get a piece of that ubiquity. There is the iPhone of drones, of vaporizers, of online business platforms, and even of guns.

The iPhone was all but non-existent before 2008, yet six years later is ubiquitous. It has altered our everyday lives in countless ways, but it is impossible to be sure which ways will have a lasting effect. Will the ability to have email updates pushed to our phone still be significant ten years from now? In fifty? Will we always claim to have “an app for that”? For how long? When we label a technology as the “iPhone of X”, we really aren’t saying why X will be significant, because we aren’t totally sure about the iPhone, either. We know or desire that there will be some longer effect in the future, but we don’t know what that may be. We have a sense that there is a something here in our moment in history, our historical context, that is significant, and yet we cannot say for sure what it is. Snowclones dance around historical context, but that doesn’t mean that there is nothing to learn from that dance. The historical specifics of any particular technology may be completely glossed over in the rush to paint a certain marketing picture. The material facts of history are not always considered, but there are important stories being told, all the same. In snowclones we see society’s technological desire, writ large.

The technological snowclone speaks to our notion of historical epochs, our sense that new technologies mark a historical transition, unique to their times in a superlative way. In many cases, it doesn’t necessarily matter that the Model T and the PC — or for another example, the Wright Flyer and the Saturn V rocket — are drastically different technologies created in completely different contexts. What matters is that each achieved a certain breakthrough, and thus launched the “automobile age,” the “computer revolution,” “the age of flight,” and the “space age,” respectively. But these epochs also betray a certain insufficiency, a deeper context missed in the symbol. We are still flying in planes, and aircraft are still evolving, even as we launch satellites into orbit. If these ages can be contemporaneous, what does that say about their relationship to each other? What does the “age of flight” mean, if today even our simplest aircraft are completely incomparable to the Wrights’ cloth and wood construction?

Consider also the “moonshot,” a phrase used today by Google X, the division of Google that explores inventions that would satisfy some larger human dream — not unlike how the Wrights satisfied the urge to fly, and the Apollo missions were the final push of a chain of inquiry stemming back to the earliest astronomers. The phrase means risk, a distant goal, and uncertain payoff outside of a wider, scientific glory. And yet in Google’s context, the phrase now describes self-driving cars and broadband-by-balloon. While both are certainly technological feats, it is difficult to say whether they would usher in a new era of human history. What does the “moonshot” mean to us today, when we are still struggling to get back to the moon? Why aren’t Google X’s “moonshots” actual, literal moonshots?

Often, while technological snowclones stay much closer to home, they maintain a distance between our current understanding of technology and any broader context — historical, economic, or political. Take, for example,the Walkman and the iPod. These two personal music players have similarities in the way they affect our ability to listen to personal music in public. These particular models so dominated our understanding of the device, that their brand names are now used generically to refer to any similar technological system. On the other hand, if we were to present these two technologies as analogous in their use by consumers, we would also need to draw their secondary effects on the means of music production and distribution into comparison as well. And there might be certain similarities: the ability for consumers to dub their own tapes threatened music industry profits, as did the mp3. But the iPod, through its relationship to the iTunes store, in some ways saved the music industry’s line of profit from the threat of the mp3 itself, a totally different technology, which is not analogous to the cassette tape. So while these devices are similar, the iPod’s relationship to online mp3 sales is a difference so profound that we have dubbed the latter the “iPod moment,” now used to analogize what iPods did for music consumption to smart watches, payment systems, newspapers, e-readers, electric cars, and “thin clients” (whatever they are). And so with all vocal similarities, silent differences are introduced as well.

Of course, the technological snowclone does not necessarily intend a literal analogy, but can be more about what we consider to be “the spirit” of invention. Consider this Sprint commercial, in which an entire canon of devices are portrayed in a “domino effect” of history, cascading from one into the next. There is certainly a technological system extending across human history. New inventions set the stage for the next wave of inventions, in the market, in manufacturing, in sub-components, and in human recognition of what is possible. But this domino effect implies analogical succession, a genealogy of technical inheritors. “Progress” is a network, not a line; the invention of the camera simply does not have anything directly to do with the invention of the cell phone — or at least, no more that it does with the invention of the e-cigarette, which is not pictured in the Sprint commercial for the obvious reason that it not considered culturally significant, part of the same inherited greatness. This Biblical, canonized chain of begetting leads, unsurprisingly, to Sprint’s newest smartphone — the descendant of a techno-historical line of David.

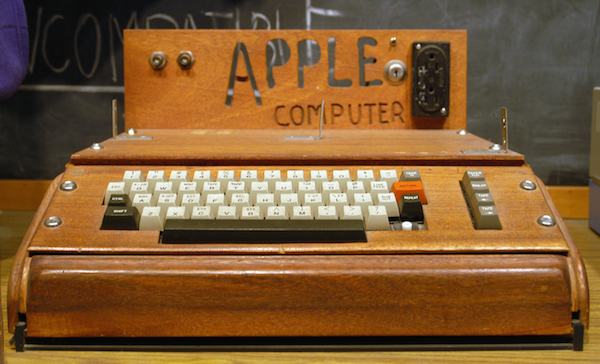

Overall, these analogies tend to portray technological objects as flat, “great gadgets of history” — attributing their importance to the devices themselves, rather than the historical context that facilitated their creation. Consider the “Homebrew Computer Club,” a loose association of PC experimenters famed for gathering in the ‘70s and ‘80s, at a time when many of them were pioneering concepts in personal computer design. The snowclones of the Homebrew Computer Club can now be found for DIY hardware, quantified self projects, law, biology, micro satellites, fab labs, drones, and robots. Just as Henry Ford did not invent the car when he built the Model T — he was a product of his context, pioneering a production model able to produce cheap cars fast enough to keep up with demand, while continuing to expand his production operations — the Homebrew Computer Club did not invent personal computers, though many members did launch computer firms. A particular Silicon Valley social milieu is also only so interesting — it is likely that if Apple Computer hadn’t produced the iPod and the iPhone, no one today would invoke the company’s founders’ hobbyist groups in the late 1970s. Certainly, no one speaks about the founders of Osborne Computer and Morrow Designs in such hallowed tones, even though they both took part in the group as well. These are the sorts of gadgets that society prefers — those with single inventors, burst upon the scene in a singular event, that then take the world by storm.

Across these modes of analogy to many, various “greatest things since sliced bread,” we interact with sometimes a little bit of historical context, sometimes a lot, and other times none. But what unites them all is that this intention is, in fact, unspoken. They reference history, and yet they are always partially fantasy. It may be asking too much of popular media to have a depth of historical analysis in its tech writing. And yet the entire record of history is often excised in the simple use of any of these snowclone analogies.

But if we can easily see what is left out, what is actually said? When wading into the convoluted process of deciding what happened in history, what was relevant and what mattered, the cognitive biases implicit in our societal storytelling are revealed. “Ubiquity,” “change,” “similarity,” “epochs,” “evolution,” and “invention,” are all stock tropes by which we explain the complicated context of history when we summarize it. These are not just lazy forms of speech and writing, but a window into our sense of time. These are the dreams of our cultural sub-conscious, and the obstacles any explanation of history must avoid. But at the same time, we are stuck with them, because even though it is easy enough to see the ways in which snowclones fail, they are what we reach for immediately. Like a nervous tick or a habit of speech, our historical concepts are part of us. Understanding our continuing technological history must avoid snowclones, but as long as that history is human, it will never fully escape them.