Ida was swaying. Around her, the party was throbbing with a more kinetic motion. Ida was not necessarily what you’d call a crucial element maintaining its pulse. Instead, she was doing some math.

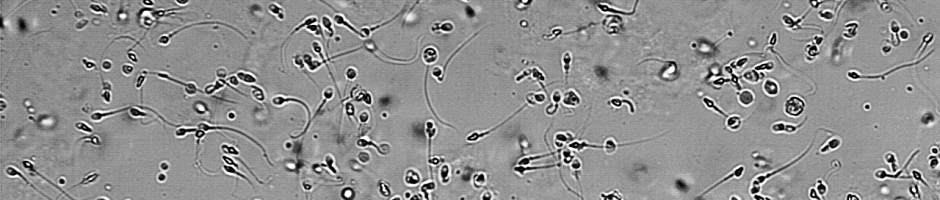

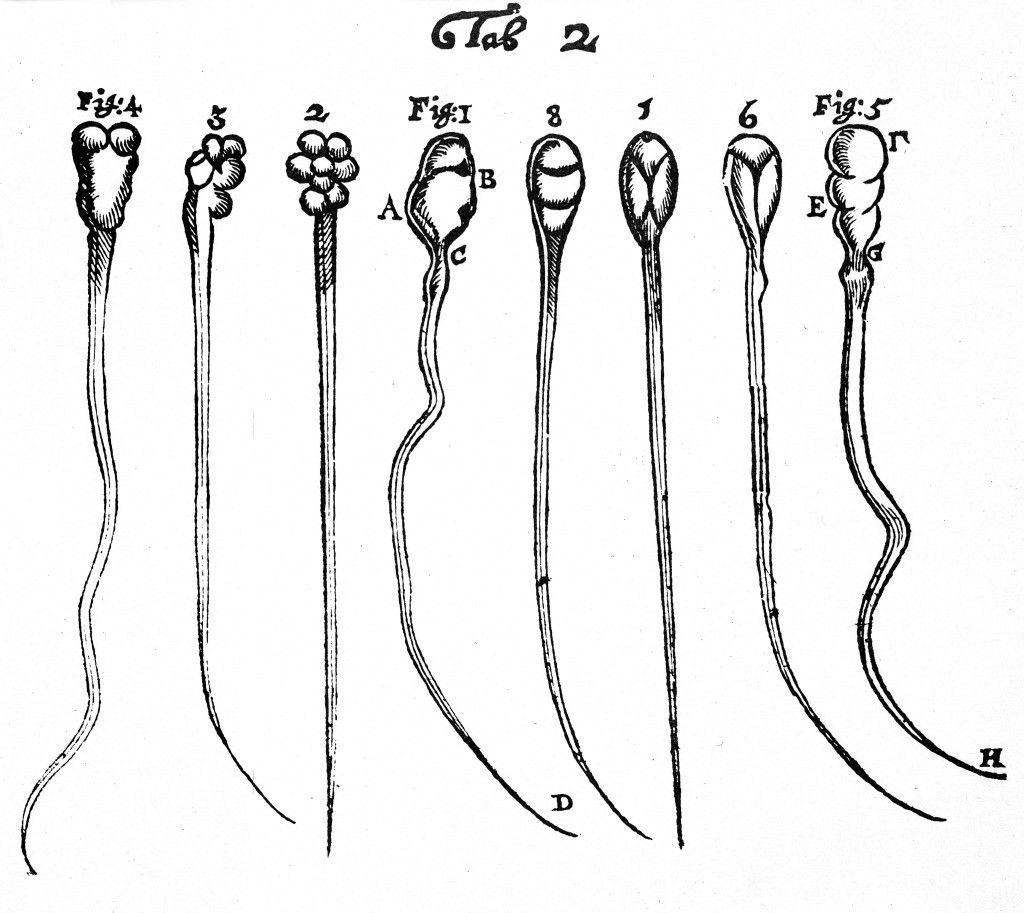

23 pairs of chromosomes in each cell. 37 trillion cells in the human body. Roughly 55 humans, probably none of which could be held up as even a semi-ideal specimen of humankind. She scrunched her nose and played with the growing hole in her too-loosely knit sweater. Then, feeling taxed by the magnitude of the numbers she was so aimlessly trying to make sense of, she wrestled her phone from her pocket. 85 fucking quadrillion useless fucking chromosomes were swimming around this shithole of a rural Arizona affair. Quadrillion.

Ida, 27, was a photographer who still clung tight to the teenage attitude of despising the town she grew up in, perhaps out of fear of it somehow seeping into her through osmosis, or perhaps because she was one of the losers who stuck around after all. From the Walmart Superstores to the megaplex movie theaters to the miles and miles of pristine black concrete parking lots—the smaller the town the bigger the everything else—Ida insisted on standing on her own self-constructed island of being. But that island, flimsy as these DIY projects tend to be, was currently sinking.

Despite her antipathy, or perhaps because of it, Ida wanted to capture the essence of this depressive little town. Her most recent photography project, a genealogy of all the town’s residents, was just wrapping up. It promised to be her ticket out to coastal cities where people had the luxury to smile condescendingly at the phrase, “salt of the earth,” while viewing photos like hers in austere white spaces filled with the silent authority of right angles. But it was also a chance for her to get at something deeper about the town, summed and averaged across all individuals. Maybe, she’d thought, that something would be a thing she didn’t hate.

The people in town raised their eyebrows at first—how Ida of her to be pursuing something so aimless, yet with a gaze always fixed so pointedly at the rest of the world. But then they resigned themselves to the harmlessness of it. Plus, they might learn some things from this new-fangled genetics stuff she was using. Ida had just received the last set of results—her own—that afternoon.

She accepted a shot of Jack Daniels from a fist-pumping stranger, quickly shifting the muscles in her face from placid stare to a smile so manically happy that only someone who knew her well would recognize how close she was to tears. She threw back the tiny plastic cup, grimaced as the heat hit the back of her throat, and shuddered as she forced the fire deep down into the pit of her stomach.

It was incomprehensible to her that some people enjoyed that stuff. If she was honest, she never had.

“You know the drill by now, champ. Need any of the ol’ supple-ment’ry materials?” chuckled Ralph Georgeson, sliding an orange-lidded clear plastic cup across the faded aquamarine desk and motioning to a pile of magazines stacked haphazardly in the corner. Their spines were cracked with use. “Bet you’ve probably got some Grade-A on that smartiepants phone o’ yers!” he said, beaming red with laughter. Ralph, in his capacity as Guardian of the Front Desk at Happiness Fertility Clinic, had already made this joke eight times today. He had made some version of it approximately 67 times the week before, and 243 times in the last month. He had gotten approximately no laughs in return, but still felt confident that it helped bolster the morale of the clinic’s downtrodden clients.

The man, well-dressed and in his mid-thirties, took the cup and nodded politely. Only someone who knew him well would detect the slightest hint of a shudder. He did, in fact, know the drill by now, and had heard Ralph’s well-intentioned cheerleadering too many times to even feel the requisite awkwardness anymore. He treaded slowly to The Room, ignoring the faint outline of the word “JIZZ” Sharpie’d onto the side of the door. It used to bother him on an aesthetic level (why couldn’t they just paint over it?), but now it stung him more deeply. That shithead kid’s jizz was a constant reminder that Stanley Westwick, rising assistant professor in the small but staunch department of Ancient Greek at the University of Kansas, could only call his jizz a sticky pile of lazy, useless fucks.

Stanley gingerly swung the door shut behind him. He emerged seven minutes and 32 seconds later (but who’s counting?), anxiously rubbing his glasses clean with his wool button-up. Ralph noticed his shirt was perfectly coordinated with the brown of his neatly-tied suede shoes. Stanley arranged himself and then waved a half-hearted but well-meaning goodbye in the direction of the aquamarine desk, glancing reluctantly at Ralph. The Guardian of the Front Desk shot back his signature toothy grin and a double thumbs-up. Atta boy, champ. Fifth time’s a charm.

Thursdays were Ralph’s favorite days at Happiness. Starting roughly two years ago he’d gotten his first promotion, putting him in charge of running the fertility tests that Maude, the main technician, conducted the other four days of the week. On Thursdays, Maude—seventy-two, considered too screechy and severe to be allowed direct contact with the sensitive Happiness clients—volunteered her services at the local abortion clinic. Four days a week she slammed the gavel down on the viability of sperm, taking the good ones to commence the process of fluorescently-lit, test tube baby-making; one day a week she saw the ones that had raced hurriedly to the finish all on their own, and abruptly cut short their automated dance of genetic fusing and splitting.

So on Thursday evenings, Ralph had the place to himself. This was when he reemerged as Fertility God of Happiness Clinic.

He had a ritual. First, he’d close up shop, popping the best album of the year—Guns N’Roses’ “Appetite for Destruction”—into the tape deck. Next he’d take out his pocket flask of Jack and take a little swig. The heat made Ralph roar alive. Appointments ended at about four-thirty, giving him until seven to do the vial-sorting, solvent mixing, and tube-checking that divided the whole day’s work neatly into winners and losers. He loved the orderliness, the Science of it: thumbs up or thumbs down. Swig.

A-brams, T. thumbs up

C-antor, J. thumbs up

E-llis, D. thumbs down (you could tell with that loose-limbed pansy!)

K-im, L. thumbs up

She’s got a smile that it seems to me/ Reminds me of childhood memories…

J-ordan, P. thumbs down

S-altzburg, R. thumbs down (society should thank him)

T-obin, A. thumbs up

Her hair reminds me of a warm safe place/ Where as a child I’d hide…

Finally, he arrived at Westwick, S. Here are those slow little pricks again. Not too many of them either! Poor sad motherfucker. Ralph took a long swig, carefully lowering the flask and pulling up the sleeve of his pristine white labcoat to wipe his mouth with his thick red flannel. He paused.

…And pray for the thunder and the rain/ To quietly pass me by…

He’d done it once before, and he could do it again. He saw the joy it brought them when they found out they’d passed, that they were viable, that they were men. The absence of failure is a beautiful thing. One last swig.

…Where do we go/ Where do we go now…

46 seconds. But who’s counting?

…Where do we go/ Sweet child o’mine…

Ralph smiled faintly to himself. Thumbs up.

“I can’t believe this is happening to me. I can’t believe you guys went this long without even being suspicious about this!” Ida screamed, wildly waving around an envelope addressed to her. Where her mother sat at the kitchen table, Ida saw only harsh streaks of primary colors. She’d always possessed a weird penchant for anger, a feeling that for her resembled a hot euphoria rising in a flash to fill all her senses to the brim. But this time euphoria was out of the question; this was a senselessness that enveloped her completely.

“Ida, just sit down, please?” her mother implored. She wiped her own tears, watched her hands as they settled down on the table, then continued. “At what point were we supposed to question whether the healthy baby we’d wanted for so long was really made the way we thought she was? Don’t blame us Ida! Blame the god-damn universe!” Now she too was shouting. Faye Westwick, like her daughter, was never one to hold back.

Ida mopped up her mingled tears and snot with the sleeve of her flannel. She stared distantly at the white mass of slime now clinging to the fibers of red wool. Her face was swollen from its own exertion.

“This is just disgusting—I’m disgusting. Who the fuck am I, Mom? Who the fuck am I made of? Who is in me?” she asked, slapping her hand repeatedly against her flat chest. Ida slumped down into a chair next to Faye and buried her head in her mother’s shoulder, sobbing uncontrollably as Faye softened the messy pile of straw-like brown hair tied haphazardly in a knot on top of her daughter’s warm head.

They sat in silence for twelve minutes.

Faye sighed. “You know, finding out you were going to be born was the happiest day of your father’s life,” she said quietly. “We’d gone to that clinic something like five times with shit luck, but he was determined that the impossible might finally happen from us just wanting it that badly. When it did, it was like he’d suddenly emerged from a coma. It was the purest joy he’d ever experienced. He’d bring that up to me sometimes, you know—even when the Huntington’s was getting really bad.”

Ida sat up abruptly, gazing absently at the various country rooster paraphernalia her mom had always insisted upon as the only appropriate kitchen decor.

She spun around to face her mother. “Well, fucking fat luck then. If only he knew what a freak was actually cooked up in that lab. And all I’ve got to show for it are two dead dudes—an alcoholic and a nutcase! What a joke.”

Ida stumbled blindly to her childhood bedroom, tears streaming placidly down her cheeks. Her vision was all shades of yellow, brown, and red; she made her way skimming her fingers along the sides of the walls. Occasionally she’d tip a framed family photo. The smiles looked especially painful tilted to the side like that. Fuck the crookedness of it all.

Ida was at this point what she referred to as “beyond wasted.” She was senseless. It was what she wanted, she thought, to match the senselessness of the universe. Entropy is always building, random shit happens, everything exists more naturally in a state of chaos than that single state of perfect neatness, right? She, and everyone else too, was just a product of a ricocheting set of arbitrary collisions.

But then there’s that other side of things: the order that matches the chaos. Cells divide without being told to, DNA peels apart, gets copied, matched up, and sealed back together again. Thousands of tiny molecules manage everything from making us symmetrical to healing our scars to cleansing our blood of the poison we ingest daily. Ida smiled faintly to herself. The thought was the only mild comfort she’d felt since she’d started viewing her own biology as abject. It was taking care of her—whatever, or whoever, it was. It was a strange bliss, finding comfort in things one would never see.

“Hi,” she said, swooping into the swirling watercolor of smiling faces drifting ceaselessly around her and plucking out a sturdy-necked passerby holding a half-full bottle of Jack.

“Hey,” he said, grinning toothily.

Ida grabbed his shoulder and whispered hot molecules of wet air into his ear.

“Fuck yes,” he smiled, giving her a verifying hungry once-over.

They grabbed their stuff and stumbled out of the apartment.

46 seconds. But who’s counting?