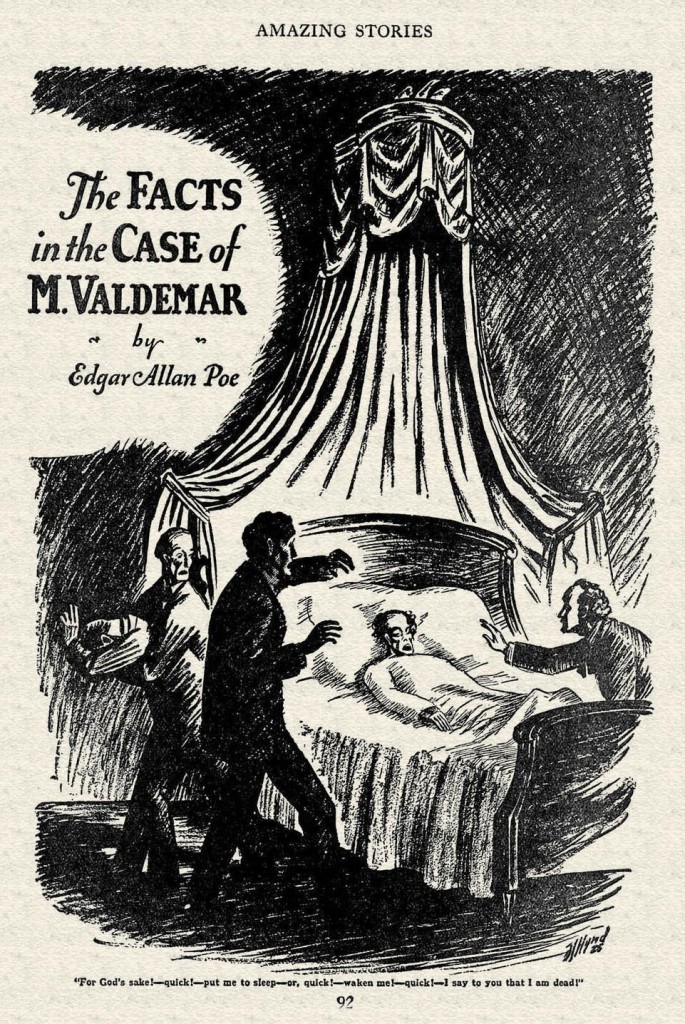

When Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar” first appeared in the December 1845 American Review, it was one of two fictional contributions out of a total of twelve articles. Titled as a medical report and placed between nonfiction essays on the Whig party and the “anti-rent” movement, contemporary readers had no definitive way to index its genre.

Poe knew this; playing with the existing hysteria around scientific experiments and affecting his own clinical tone, he successfully fooled readers, who couldn’t tell whether the story was fiction or fact. Even those aware of the magazine’s eclectic format and Poe’s literary reputation still doubted the story’s fictitiousness. Days after Valdemar’s initial publication, the New York Tribune commented that the piece “puzzled” its readers as “a pretty good specimen of Poe’s style of giving an air of reality to fictions.”

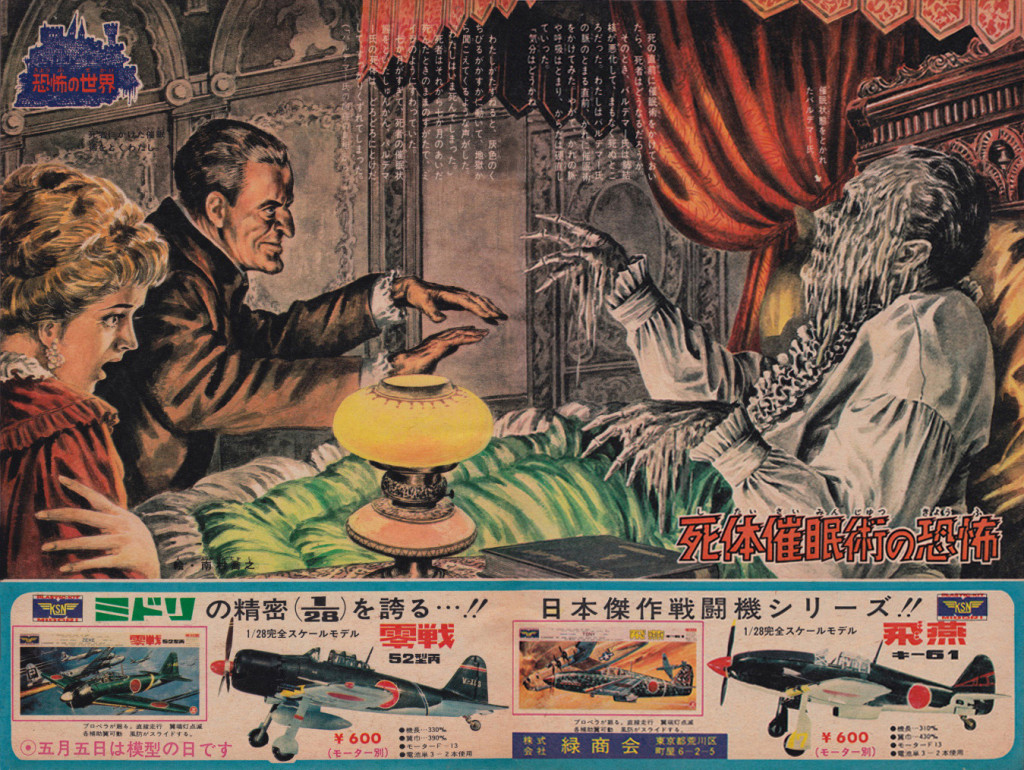

Set three months prior, in the suburb of Harlem north of New York City, the case recounts the “extraordinary circumstances” surrounding a bold mesmeric experiment. Its narrator, known only as “P—,” decides to mesmerize his dying friend, a reputable but modest author by the name of M. Ernest Valdemar. As in a typical mesmeric experiment, the influence of P—’s will acts invisibly on Valdemar’s to suspend him in a hypnotic trance. But instead of waking after several moments, the moribund Valdemar remains suspended on the edge of death—what Poe calls in articulo mortis—for a full seven months. When P—finally attempts to wake Valdemar from his trance, his rotting body crumbles into “a nearly liquid mass…of loathsome — of detestable putrescence.” Like so many of Poe’s tales, the short story ends in an implosion. But as far as Poe’s readers were concerned, Valdemar’s case was far from closed.

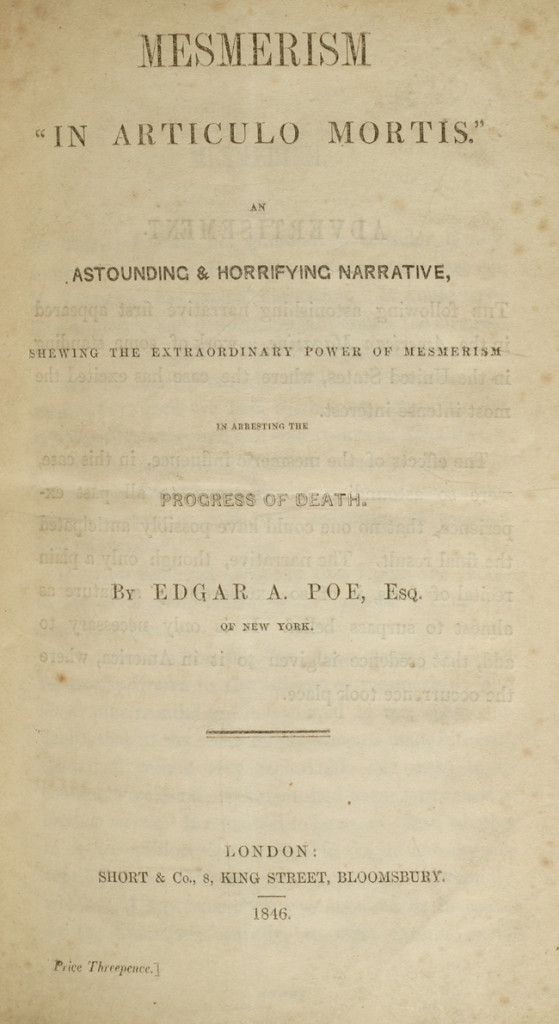

While today’s reader would never read this story as a scientific case, many of Poe’s contemporaries did. In New York, the poet Sarah Helen Whitman wrote to a friend inquiring whether Poe’s mesmeric tales were based on actual occurrences. Not long after, the poet Elizabeth Barrett Barrett wrote Poe from London explaining that the story was “going the round of the newspapers…throwing us all into ‘most admired disorder,’ and dreadful doubts as to whether ‘it can be true,’ as the children say of ghost stories.” One mesmeric enthusiast from Scotland even paid to have his letter sent across the Atlantic so that he could ask Poe, “for the sake of Science & of truth,” whether the “pamphlet lately published in London [i.e. ‘Valdemar’]” was “genuine.”

How could Poe’s readers wonder whether such a fabulous story was true? What cues indexed his story as both a compelling literary work and a rapturous scientific report? And what does that say about how we distinguish between science and fiction today?

At the time Poe was writing, neither the category of the scientific nor the literary bore the authoritative force they do today, leading his readers to hesitate between credulous and incredulous interpretations of Valdemar. The contentious reception of Valdemar’s case—whether it was read as science, as literature, or as a debunked hoax—rested on the contexts of its printing. This is the story of how Poe took advantage of the fluid and anxious interplay of periodical culture and popular science in antebellum America to reveal the way their authority depended, above all else, on the production of doubt.

Reprinting Authority

Perhaps more than anyone else’s that era, Poe’s itinerant career––his magazine-work in every literary capital and across various forms of publishing––paralleled the dislocating forces of an unauthorized literary marketplace, operating in the absence of intellectual property law. Literary periodicals in the US made almost no money in a market dominated by cheap reprints of books from Britain and unauthorized reprints of domestic successes. As Meredith McGill explains in her landmark study, American Literature and the Culture of Reprinting 1834-1853, the space for American literature in Poe’s time, and even the concept of the literary, was contingent and highly contested, subject to frequent debate in courts, in Congress, and in the newspapers.

Understanding his underdetermined authorial agency in this predatory market, Poe strategically appealed to this decentralized literary culture through a mix of mass and high cultural styles. He invented a reflexive and flexible aesthetic—one that was suited to the dislocation of space, identity, and modes of address brought about in the unauthorized reprintings of his work. Like many of today’s content-generating sites seeking to maximize their profits from Facebook traffic, Poe even ‘updated’ the headlines of his stories and obscured specifying details so as to maximize their appeal no matter where they appeared.

Poe’s editors likewise published texts without reference to their author, place of origin, or genre. These canny editors orchestrated an atmosphere of doubt around “click-bait” work as a means of turning popular interest into magazine sales. Poe knew that his story would only be relevant so long as it operated––as his other hoaxes did––under a sign of indeterminacy.

Two weeks after its first publication, he prefaced his own reprinting of Valdemar in the December 20 issue of the Broadway Journal, the magazine that he edited, with the following editorial note:

An article of ours, thus entitled, was published in the last number of Mr. Colton’s ‘American Review,’ and has given rise to some discussion––especially in regard to the truth or falsity of the statements made. It does not become us, of course, to offer one word on the point at issue. We have been requested to reprint the article, and do so with pleasure. We leave it to speak for itself. We may observe, however, that there are a certain class of people who pride themselves upon Doubt, as a profession.––Ed. B.J.

Poe’s impartial editorial address established that the power to persuade readers resided not in the editor’s judgment but in the testimony of the article itself. These “fictions that refer primary to themselves for their authority,” as McGill puts it, are designed to deflect and redirect the desire for context to the inside of the text itself. This “portability” compensated for the story’s eventual submission to the decontextualizing hazards of reprint culture.

But this lack of closure also encouraged the reprinting of his tales, outsourcing editorial judgment to the tribunal of the general public. In this way, reprint culture traded not only on the dislocation of texts from authors but also on the speculation and hesitation of its readers. The air of controversy gets repackaged as an added value of the reprint.

This economic logic guided Poe’s style. To continue to sell sensational literature, Poe had to continually raise the stakes of his grotesque and fantastic literary productions. Almost all his tales narrate an exceptional event that exceeds the rational possibilities of their premise; these tactics of exaggeration attracted new readers––and renewed attention from the press. His “stylistic extremity,” to borrow McGill’s phrasing, was “an engine of circulation.”

The design of Valdemar is exemplary of this extremity. Written at a time when the public was captivated by fantastic experiments claiming to reanimate the corpses of animals and human beings, the timeliness of its spectacular subject matter ensured its sensational reception. Valdemar extrapolated from the limits of a science that understood itself as transforming the limits of human experience and its exceptional turn of events guaranteed it would hold print culture’s “general interest.” What was at stake, for some readers, was the meaning of life itself.

Mesmeric Sensation

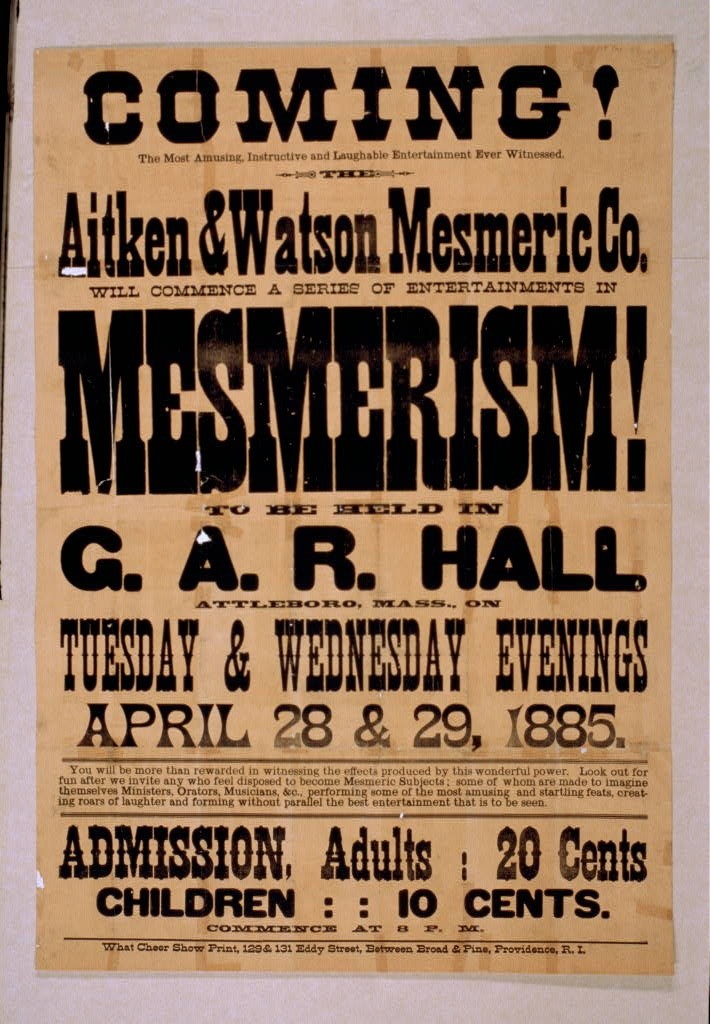

Mesmerism was introduced to the United States in 1836 by the Frenchman Charles Poyen, who offered to display its effects to the curious onlookers of New England free of charge. Poyen would plunge his subjects into a “magnetic sleep” that allowed for the unspoken communication of thoughts between the mesmerizer and his subject. Unlike in Europe, where magnetic sciences like mesmerism targeted aristocratic coteries, mesmerism swept across America’s middle classes at a time when the pursuit of science was changing in its nature from a polite diversion—practiced in private, elite circles—to a mass vehicle for entertainment.

During the 1830s and 1840s when Poe was writing, the cultural authority of science was not inevitable. The panoply of amateur sciences had yet to be tamed and professionalized: learned pigs were paraded to audiences one night, fireproof ladies the next. These popular sciences often aimed, as spectacles like theater and the opera did, to involve their audiences in fully embodied experiences. Thousands attended the expressive lectures of mesmerism’s eager new practitioners, who investigated higher powers such as clairvoyance and telepathy.

Soon the press took note of mesmerism’s impressive accounts of medical treatments and special powers. As specialized publications praising the wonders of mesmeric sciences started to circulate in print, so too did exposés revealing its deceptions. In response to these detractors, mesmerism’s defenders penned even more elaborate tracts praising the science’s promise to bring greater perfection to human society. Contrary to our associations of scientific writing with dry impartiality, scientific writing in the 19th century was often literary. From the panoramic landscapes conjured by Humboldt to the Victorian lyricism of Darwin, scientific texts used simile, metaphor, personal observations, and even quotations from Shakespeare as evidence.

These scientific and, retrospectively, pseudo-scientific texts were themselves part of complex power negotiations, not only on behalf of their own authority but also on behalf of the institutional authority of science itself. “The new practitioners, whether mesmerists, hypnotists or spiritualists, were as anxious as their predecessors to convey the impression that they [practiced] ‘empirically’, and they were often lavish with strikingly precise clinical descriptions,” explains the French critic Antoine Faivre.

But even at the height of its popularity, mesmerism’s incredible claims always labored under uncertainty and hesitancy. As the practice lacked formal standards, viewers of its spectacles had no way of telling whether what they were seeing was a mesmeric truth or its forgery; nor could readers of mesmeric texts necessarily distinguish between the clairvoyant testimony of an impostor or the reliable description of an honest gentleman of science. Doubt was assumed as the precondition for all readers of mesmeric literature and built into the text’s address was the need to convert skeptical readers into credulous believers. But securing epistemological stability was no easy task for a science whose literary goal was to impress upon its readers the subjective states of other peoples’ minds.

Poe borrowed, exaggerated and distorted the stylistic techniques of these testimonials to authorize Valdemar, if not as a truthful case, then at the least as an authentic mesmeric claim––one indexed by this ever-present polarity of credulity and incredulity. Valdemar, in particular, draws heavily from the Reverend Chauncey Hare Townshend’s Facts on Mesmerism, a British text that went through five American printings from 1840 to 1844. Poe even reviewed the book favorably for his Broadway Journal as “one of the most truly profound and philosophical works of the day—a work to be valued properly in a day to come.” P––, the narrator of Valdemar, imitates Townshend’s performance of medical authority, with his clinical measured tone, use of temporal markers, and deployment of small details.

As with Townshend’s acknowledgement of his reader’s doubt, Poe builds the reader’s skeptical response into the story by conceding in its first paragraph that the case of Valdemar excited “very naturally, a great deal of disbelief.” Poe’s narrator positions himself as a modest witness close to the events at hand, aligning himself with the reader’s own incredulity: “It is now rendered necessary that I give the facts––as far as I comprehend them myself.” In this way, P— does not seek to convince the reader of his case, but rather, to corroborate its improbable details.

Soon mesmerists began to read and cite the case to prove their new science’s incredible powers, invoking Poe as a reputable figure of authoritative judgment to do so.

Unreliable Narrators

Anyone, it seemed, could ride the faddish wave of mesmeric sensation––as a calling, a hobby, or a joke. In 1843 there were supposedly over 200 practitioners of mesmerism in Boston alone. This made mesmerism particularly vulnerable not only to private errors of the senses but to the public errors of disreputable humbugs, whose misleading claims on behalf of the heterodox science had the potential to derail its credibility. With such a broad swath of society claiming allegiance with its methods, mesmerists had a difficult time securing the authority of a science liable to err.

Citing Valdemar as an exemplary mesmeric case certainly didn’t help their cause. But tracing their citations reveals the norms at play—what counted as factual evidence and as the proper conditions for scientific investigation—in antebellum popular science.

Dr. Robert Collyer, a popular traveling lecturer, was one of many incompetent preachers of the new mesmeric faith. He readily bit Poe’s bait, writing to the Broadway Journal on December 16 in reference to “the extraordinary case of M. ‘Valdemar’.” While the “Editorial Miscellany” of the December 27 Broadway Journal reprinted Dr. Collyer’s letter to mock his foolishness, his letter can also be gleaned for insights into the conventions for producing scientific knowledge.

DEAR SIR —

Your account of M. Valdemar’s Case has been universally copied in this city, and has created a very great sensation. It requires from me no apology, in stating, that I have not the least doubt of the possibility of such a phenomenon; for, I did actually restore to active animation a person who died from excessive drinking of ardent spirits. […] I will give you the detailed account on your reply to this, which I require for publication, in order to put at rest the growing impression that your account is merely a splendid creation of your own brain, not having any truth in fact.

My dear sir, I have battled the storm of public derision too long on the subject of Mesmerism, to be now found in the rear ranks — though I have not publicly lectured for more than two years, I have steadily made it a subject of deep investigation. I sent the account to my friend Dr. Elliotson of London; also to the “Zoist,” — to which journal I have regularly contributed. Your early reply will oblige, which I will publish, with your consent, in connection with the case I have referred to.

Unlike general interest magazines, which promoted Poe’s story for its great “literary merit” to garner sales, Collyer hoped to publish Poe’s “account” alongside his own for scientific ends. He wished to redeem mesmerism from its “storm of public derision” through linking together a network of epistolary assent of mutually reinforcing gentlemanly signatures: his own, Dr. Elliotson’s remarks, and the “Zoist,” a widely read journal on magnetism.

In Collyer’s ideal image of consensus, equal selves––professional and elite gentleman––signed onto these authentic cases. By submitting one’s signature, along with one’s testimonial, one’s reputation was on the line. “The more men that signed their reputations onto a case, the stronger its authority. Not unlike today’s peer review culture, this culture of assent relied on the strength and numbers of its witnesses.

For instance, when Orson Squire Fowler, famed phrenologist and editor of the American Phrenological Journal, had to retract his reprinting of “Mesmeric Revelation,” another one of Poe’s mesmeric tales, a couple months prior, he wrote that he was persuaded to insert the article by the commendation of a practicing mesmerist and by the scientifically-engaged context of Poe’s “literary clique.” For men like Collyer and Fowler, the scientific values of public gentleman were linked to their moral and ethical virtues. It was the reputation of these men that induced credulity, not the contents of the article itself. Curiously, the words literary and fictional don’t occur anywhere in Fowler’s classification of the text. Even after retracting the story, Fowler understands Poe’s report as bad science, not as good literature.

Like a peer-reviewed experiment demanding to be replicated, the controversy surrounding Valdemar kept reproducing itself. The next month, London papers reprinted Valdemar as a sensational story from abroad, though not without first retitling the story as “Mesmerism in America: Astounding and Horrifying Narrative.” On January 10, 1846 the Popular Record of Modern Science reprinted the story from the Morning Post (which had reprinted the story from the prestigious Sunday Times), under a new title, “Mesmerism in America. Death of M. Valdemar of New York.” One might think, judging by this new headline, that Poe’s gruesome tale was the obituary of a well-respected and urbane gentleman—which it seems that the Record did. The Record even appended a postscript following their printing of the story explaining their predilection for the story’s “testimony.”

The most favourable circumstances in support of it, consist in the fact that credence is understood to be given to it at New York… It will therefore appear that there must have been too many parties concerned to render prolonged deception practicable.

The angry excitement and various rumours which have at length rendered a public statement necessary, are also sufficient to show that something extraordinary must have taken place…

The Record understood the story’s definition of a real place and its polite elision of professional identifications as evidence of its authority. Its reportorial investigation was meant to corroborate, not challenge, the testimony of these witnesses. The Record saw the presence of controversy as a testament to the sensational nature of mesmeric truths.

It should come as no surprise that four months later, the Record’s editor issued a long retraction. Like Collyer and Fowler, the Record presented an image of science as an ethical genre, grounded not in style but in social reputation. In the Record’s calculus of error, truth and falsity were linked to the reputation of the author, and Poe’s signing of his name onto a fake case would, upon its detection, “exclude him from society.”

But of course, Poe was never punished for his queering of the gentlemanly act of peer review. In a reprinting culture where so many fictions took on the “air of reality,” all depersonalized mass communications, whether literary or mesmeric, were liable to interceptions by a plurality of readers. Poe understood mesmerism not as a fluid for harmonious connection, but as a metaphor to reveal the instability, disintegration, and interruption inherent to all literary technologies.

His submission of this “prolonged deception” into the scientific scene subverted the desire for shared knowledge and expertise, and at the same time, reinforced the process for learning how to know. In this sense, Poe reveals himself as a canny sociologist of science, actively managing the controversy around his story and acutely analyzing its craft.

After all, Poe had already written the Ur-case study of scientific controversy within Valdemar. The story opens by anticipating its own sensational reception: “Of course I shall not pretend to consider it any matter for wonder, that the extraordinary case of M. Valdemar has excited discussion.”

We leave it to speak for itself.