My parents genetically modify corn for Monsanto. They are geneticists, technically, and work on patenting new methods and technologies for engineering corn DNA. I’d like to share with you some memories I have of childhood around Monsanto.

1.

I was slightly larger than an average toddler, walking behind my mother, who was wearing blue jeans and a long sleeve Hanes T-shirt and a straw hat. These were her field clothes. We were walking into one of “her fields” — a field of corn for which her team had created the seed. The plants were much taller than me; it must have been mid-summer. I didn’t really like being there, because the leaves of the corn plants were sharp and scratched me (this was why my mother was covered this way) and because it was so hot and unbearably humid. The rows of corn were planted far enough apart for one adult person to walk; they created no shade for a child. My mother was stapling paper bags over the ears of corn that have blossomed, tucking in all of the silk, trapping them so insects couldn’t get in, and so my mother could cross-pollinate the plants by hand.

2.

The corn was not just in the field, but in our home. The corn was not usually food. What is it that compels upper-middle class families to acquire large wood and glass cabinets to place in unused dining rooms, and then fill them with unused objects? Our cabinet was filled with corn objects — mostly fancy dinnerware that featured corn. There were corn salt and pepper shakers. There was a large porcelain serving platter, shaped and painted to look like a flattened and oversized ear of corn. There was a lovely terra cotta corn water pitcher that my mom actually took out and used sometimes, at particularly stressful dinner parties. There were many corn figurines. My mother reserved a corner on the second shelf for her great-grandmother’s incredibly beautiful and delicate teacups, and carved out the drawer space as the designated stash of table linens. Probably around age 11 I began, not even ironically, to call the glass cabinet the “corn shrine.”

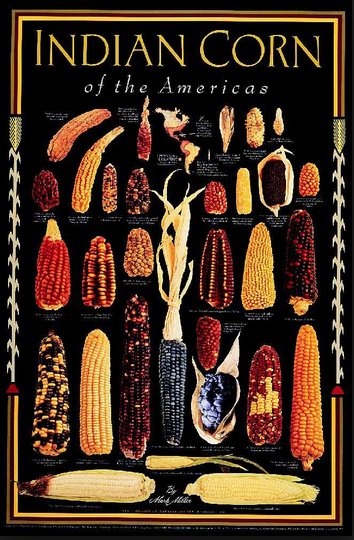

The corn shrine was not even close to being the only corn décor in our house. You’re kidding yourself if you think we didn’t have corn pillows, candles, wall hangings, posters, and T-shirts. My mother had corn earrings, my father probably had a corn tie (although if he did, he didn’t wear it). This was a poster that we had framed, displayed prominently in our kitchen:

We had ceramic tiles next to the front door to our house, displaying our address. They were painted with the number of the house surrounded by a field of corn blowing in the wind, on a blue sky day.

3.

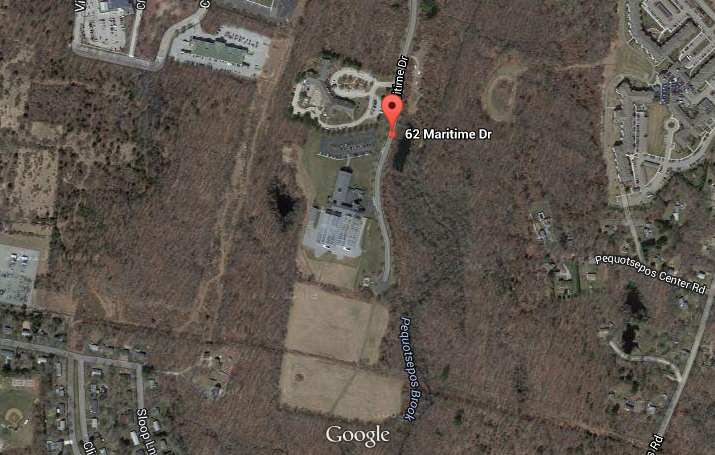

My parents’ corn fields, and this particular branch of Monsanto, are in Mystic, Connecticut, of Mystic Pizza and Julia Roberts fame, my hometown. This is what it looks like on Google Maps via satellite.

Here you can see the greenhouses and the cornfields, and the neighboring swampy pond. It is a small operation, but I guess not insignificantly sized in the grand scheme of all Mystic real estate.

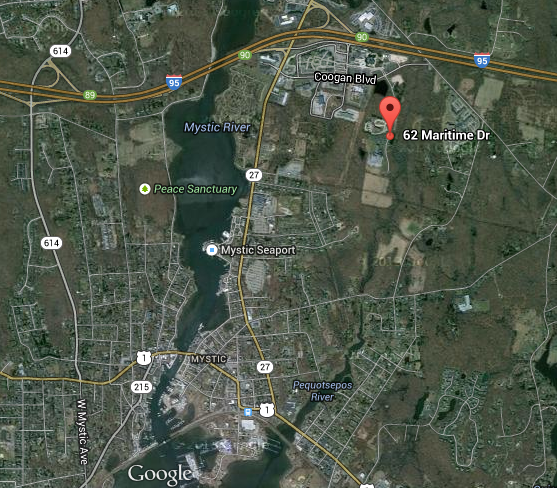

Here is Monsanto and the rest of Mystic. My childhood home is just cropped out of this screencap. Can you see the Peace Sanctuary? That’s where I smoked weed as a teenager. And do you see how Routes 215, 1, and 614 form a sort of chain just west of the river? That was where I loved to drive around in my parents Passat station wagon, after smoking at the Peace Sanctuary.

4.

In second or third grade we had to write something or other about our parents’ professions. We had to make this writing into a booklet. Since genetic modification is too complex for the average 7-year-old to understand, let alone communicate in a stapled printer paper booklet, my parents told me they were “corn doctors.” I remember writing something about how Native Americans understood corn to be a sacred mother because it fed all the people, and how my parents were somehow a part of this process. I remember drawing an ear of corn with a woman’s face in it on the cover of my booklet, not unlike the old woman’s face in the weeping willow that plays an oh-so-problematic role in Disney’s Pocahontas.

5.

I remember a family picnic held in the large clearing to the southeast of the building. Many people who worked with my parents had children the same age as my brother and I, and the company naturally rented out an inflatable bouncy castle and slide, which was tremendous fun. In an attempt to cut the line of other kids making their way up the slide, I had the brilliant idea of pretending to escort smaller children in the climb up, and carry them down the slide on my lap. It worked. I took more turns than anyone else. There were hot dogs.

6.

As you can see on the satellite photograph, the Monsanto fields bordered a forest pond on the west, and a marshy stream area to the east. The fields themselves I’m sure were tilled and leveled and drained and RoundUp Ready’d to the exact correct conditions needed for producing experimental corn, but the marsh and the woods had particular ways of haunting the land anyway.

One summer in my early adolescence, my parents both confirmed seeing a huge snapping turtle making its way through the rows of corn, much like I had often done following my mother. In my memory of their story, the turtle is around 5 feet long, tail to head, but this can’t be true. Snappers frequented marshes and ponds around the area — I had seen small ones myself in the nature preserve area to the southeast of the Monsanto site. My parents weren’t surprised to find the snapping turtle there in the field. It was huge, they said, so it must be old. It must be confused.

7.

As a sevenish to 11ish year old I had a long-term obsession with Sculpey — the clay that would harden when baked in the oven and came in a rainbow of colors. I used it mostly to make beads and miniature household objects, but my dad, especially in the early days of my clay infatuation, would often sit with me and join in my Sculpey-craft. He liked making miniature food. One of the first times I played with the clay, my dad created a perfectly adorable ear of corn. He formed the yellow kernels by rolling tiny balls of yellow clay between his thumb and index finger, then stacking and pressing them into a larger oblong yellow piece. He rolled out two leaves of green clay and texturized them with a toothpick, drawing in the veins, then curled them with precision around the yellow ear. The pointed tips of the leaves curved out from the ear jauntily. He rolled out impossibly thin brown clay snakes for the silk, and nestled them at the top of the ear. “Look!” my dad implored me when he was done making the corn. The clay model was utterly perfect.

8.

I loved going to the Monsanto building with my parents. In order to enter, you were required to type out two codes on a keypad, and swipe an ID badge. Even if you completed this, after hours, an alarm would sound, disabled by another separate code. This brought you to a sort of lobby, to the right of which was the office supply cabinet, which held many colors of Sharpies, and those delightful blue lab notebooks with the numbered pages. I took liberally from the office supply cabinet, until my parents notified me that each of the delightful blue notebooks cost round $20.

9.

The floor tiles in the main hallway at Monsanto are laid out in a peculiar pattern. There are multi-colored linoleum tiles laid out among white linoleum tiles, and the multi-colored tiles form a corn stalk, and then an ear, and then a double helix, linked like DNA.

10.

My parents began working at 62 Maritime Drive I think in 1991, when it was Dekalb Genetics Corporation. Monsanto bought out Dekalb in 1998. On the day that power turned over from the smaller company to the huge agro conglomerate, all of the employees at 62 Maritime Drive wore black. My mother came downstairs that morning in a black long-sleeved t-shirt and black jeans. My father wore a black button-down and black slacks.

11.

I barely remember the Monsanto fields in Maui. They were the least interesting part of a family vacation we took so my parents could visit their fields there. I remember only that I was surprised by Maui’s barrenness, even though my parents told me that part of the island was a desert. That’s why the fields are there, they said, because we are testing for drought resistance. My visit to the cornfield itself is entirely unmemorable, except for the chain link fence that surrounded the whole of it, and the way it remains connected in my mind to the following:

The first iceberg salad I ever had, just after that visit in a restaurant with heavy white tablecloths, with bacon and blue cheese dressing, served classically in a wedge.

The repulsive burning smell that pervaded the few miles between our hotel and the field. The smell was, according to my father, the burning sugar cane, as there was a large processing plant on the coast. I do not remember seeing the factory itself, but the smoke hung over the road and between the cliffs like San Francisco fog.

12.

For the summer between sophomore and junior year in high school, I worked in the Monsanto community garden, weeding, transplanting, and harvesting mostly heirloom garden plants. A bunch of 62 Maritime Drive workers felt connected to the local or slow foods movement, and they wanted this garden to grow plants for themselves and donate the extra to a local food bank — either consciously or unconsciously to offset the Monsanto Factor, I don’t know. I weeded and picked, and listened to Elliott Smith on my iPod. I was working in the garden to fulfill community service requirements that my high school magnet program required. It was alright except for once getting sunstroke, and once accidentally picking a winter squash in the height of summer, because I had mistaken it for something else. I was cussed out by a notoriously bitchy longtime Monsanto employee for not having my squash-ID skills down pat. I also got to accompany a different employee on the 30-minute drive from the site to the food bank. She had Bruce Springsteen CDs in her car, and it was there in this virtual stranger’s passenger seat that I first heard “Born to Run.” Go figure.

This essay was first published in SMOG, a multimedia online publication.