Ask a six-year-old why dinosaurs are fantastic, and she’ll fire back with gusto. The fearsome teeth of Spinosaurus. The neverending neck of Mamenchisaurus. The evolution of flight among the close cousins of thunderous T. rex.

Put this way, dinosaurs seem so self-evidently fascinating that you wonder why interest in them tends to fade with age. Our imaginations are especially active as kids, as our brains work in overdrive to sort fact from fiction. Dinosaurs toe that line magnificently: Unlike anything on this Earth, they’re like monsters—but real. They’re firmly extinct (unless you count birds), but vividly alive in the theatre of our imaginations.

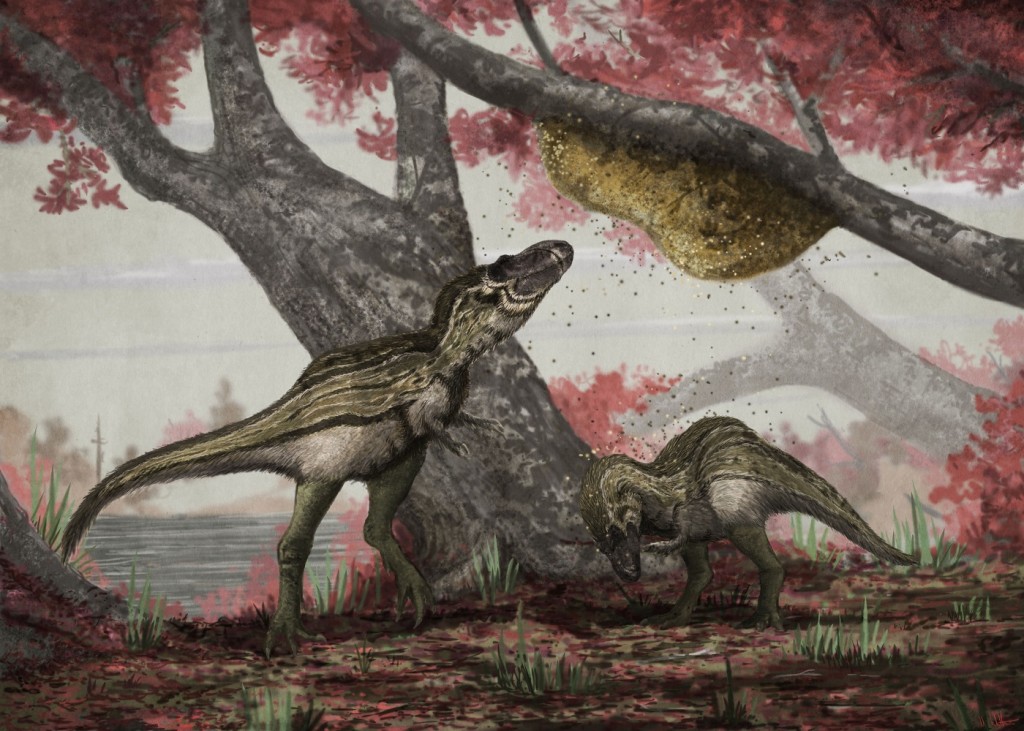

We think we know dinosaurs from their fossils, the mineralized bones scientists uncover and describe. But the dinosaurs that ignite most imaginations are the ones we know from books, museum graphics, and film. Art—paleoart—is what gives these extinct animals sinew, skin, scales, and feathers. Pencil, paint, or Photoshop “restorations” show dinosaurs feeding and mating, hunting and resting, fully alive on Earth 65 million years ago or more. Chances are, when you think “T. rex,” you’re actually thinking of the work of a paleoartist.

Paleoartists do much to keep dinosaurs scratching at the popular imagination, yet they are a marginalized class in both paleontology and art. Though the best paleoartwork is rigorously faithful to the fossil record, it inherently tests the bounds of what science can know. And its apparent intersections with fantasy often complicate its entry to the gallery world.

Why do these unsung illustrators do what they do? And how? Three prominent working paleoartists shared their thoughts on the field with Method Quarterly. Though there are surprising divergences among them, Douglas Henderson, Mark Witton, and Emily Willoughby held one trait in common: A fascination that started in childhood, but never went away. Here are the highly edited versions of my conversations with them:

Douglas Henderson

Dinosaurs were part of the culture when I was growing up in the 1950’s—and I was drawn to them, being given books about dinosaurs on birthdays, playing with wax models, collecting dinosaur stamps. I remember my parents taking me to the Smithsonian and walking down the length of the mounted fossil Diplodocus skeleton in the Dinosaur Hall. I remember the first TV showing of the 1933 classic King Kong. I drew them from my earliest years and never quite put them aside.

I aimed for book illustration once my work seemed good enough, though the same sort of work applied to museum exhibits, murals, posters and even design work for movies and animation projects. Hollywood, hands down, paid best of all, while asking for the least credible work.

I don’t consider myself a paleontologist. Paleoart is not science—it expresses ideas in a way unique to each artist’s personal touch, the least repeatable approach to reaching an end result. If I’m asked to do something, I try to read what I can find or talk to someone familiar with the subject (usually the person asking for the work in the first place), seeing what hypothetical reconstructions have been done (usually based on some better known similar animal), eventually showing preliminary work to those prepared to say yeah or nay.

Fortunately, there’s still some room for artistic licenses. You can pick a color, with or without a good reason. I think back to when I was a kid playing in creeks and woods, hunting crayfish and eels, frogs, turtles, lizards and snakes. Something of these experiences, this first contact with real nature, evolved to give me? some personal insight to dry scientific data.

From my experience, in time, more will be known and your work will become nonsense. I did a number of illustrations of a little dinosaur believed to have lived in Petrified Forest National Park during the Triassic over the years, based only on some fossil teeth. More recently, the teeth were determined to have come from an aetosaur, an armored thecodont—a completely different animal.

I do feel a constraint to keep the work accurate or sufficiently plausible and not drift off into fantasy. I like science fiction and have done work along that line, but want to keep the genre separate.

Personally, I don’t see other working artists looking down on those who do paleoart. [But] it is death to walk into [an art] gallery with a dinosaur work under your arm. Whether paleoart is burdened by some association with fantasy art, empirical science, or some unforgivable nerdiness, the fine-art gatekeepers want nothing to do with it. Paleoart travels in its own odd little orbit between two camps, not altogether embraced by the sciences or the arts. Paleoart is some sort of eddy in the stream of things.

Mark Witton

From an artistic sense, I’m self taught. My drawing subjects were a little broader before 1993 (when I was 9 years old), but then Jurassic Park came out, and that spurned an already keen interest into dinosaurs and similar animals into overdrive.

I publish research papers on fossil animals as well as restoring them. Having a PhD in studies of extinct animals gives [me] a good grounding in the scientific methodology, subject matter, and research techniques that underpin paleoartworks.

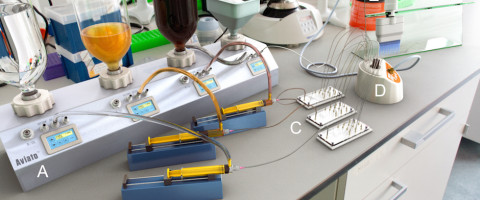

The translation of fossil specimen to restored animal is simple, at least in theory. Fossils provide a skeletal framework which inform proportions and, by comparisons with modern relatives, some aspects of their muscular system. Once the skeleton is put back together, and musculature is applied, we have a basic model onto which skin, scales, feathers, fur, etcetera can be placed.

This process is not always straightforward. Animals are three-dimensional objects, [and] their skeletons do not always fit together in ways we might expect. Something seemingly meaningless—like articulating a rib bone incorrectly—can alter aspects like the orientation of the shoulder, and mean the difference between sprawled or upright forelimb postures. We can look to other data, like fossil trackways, to help place the limbs of our restored skeletons, but even they are not always as helpful as we might like.

Good paleoartists don’t just make missing animal components up. [They] should be using as little imagination as possible: they should be able to point to a reference point for all of the major decisions surrounding their work, and justify how it ties into scientific opinions on their subject matter. There is a ‘right’ and ‘wrong.’ Far more people will look at illustrations than they do any text, so it has to suit the story being presented [in the] science.

A fossil of a completely-known close relative to the subject species might be consulted to fill in some gaps. If that doesn’t help, then characteristics of a wider group might be looked at. Of course, this does have a limit: especially poorly-known animals cannot be restored with any degree of certainty. Things like color, patterning, distribution of soft-tissues etc. rarely preserve. That’s where we switch datasets from fossils to modern animals. Using hypotheses about the lifestyle and ecologies of extinct animals, we look for suitable modern analogues.

It’s also fun to consider environmental effects on animals, reflecting where they’re depicted and what they’re meant to be doing. Should their feet be wet or muddy? Should they [have] detritus matted into their pelage? These are the sort of details we see on modern wild animals, and introducing them to palaeoart helps make images seem that little more realistic.

It does seem difficult for us to shake the label of creating art ‘just for kids.’ So many museums and publishers have little regard for the artists who have moved paleoart along, and instead frequently employ people to ‘redo’ existing pieces. It doesn’t help that a lot of paleoart depicts animals leaping at viewers with bared teeth and slashing claws, or else focuses on ridiculous scenes of violence which have little bearing on real-life. These works tend to overshadow more interesting and sophisticated approaches to paleoart, which are essentially comparable in refinement to traditional natural history art: they just feature extinct species, instead of modern ones.

Emily Willoughby

I was into dinosaurs as much as any other kid, but the long-term scientific interest was rekindled in the early 2000s with the new feathered dinosaur discoveries in China. That was when I was in high school, and at that point my central passion was evolutionary theory and its mechanisms. Learning about the relationship between dinosaurs and birds—which at that point was becoming much less hypothetical—was totally absorbing to me, and the doodles, sketches, and later more serious artwork followed.

There is a prevailing stereotype that scientific illustration is devoid of creativity and affect, but a quick look at many currently working paleoartists quickly puts that myth to rest. I’ve intentionally strived to inject a certain amount of personality and emotion into my own paleoart. The “story” is a major part of that. Each fossil specimen represents an individual animal with its own experiences and set of behaviors that made it unique. What was it like? How did it die? More importantly, how did it live? In my view, a piece of paleoart successfully tells this “story” if it imputes the animal as a unique individual to the viewer, and not just a clinical representative of a genus.

Restorations must take the totality of research into account for the greatest accuracy. My starting point is a skeletal diagram, if one exists. If one does not, then examining the original research and any published photographs of the fossil is the best way to go. From there, researching related species, contemporaneous species, and the animal’s environment usually comes next. If the material is very scant or distorted, inference from related taxa via phylogenetic bracketing rules the decisions on how to restore it.

Melanosome studies are giving illustrators an increasing degree of guidance on feather coloration, but for the great many more taxa for which this is unknown and unknowable, inference from ecological niche and extant analogues is the next best thing. For example, I would never restore a flightless dromaeosaur with bright blue and green plumage, because such a predator would need to stay out of sight from prey and predator alike. What modern predatory bird is brightly-colored? Hawks, falcons, and eagles tend to be made of earth tones: browns, greys, black and white.

I wouldn’t say that there’s any specific point where research ends and imagination begins—in every case, the two are integrated intimately from start to finish. Even for dinosaurs like Microraptor where we know an extraordinary amount about them, right down to the color of their feathers, there’s endless potential for variety in scenario, pose, composition, and personality.

If I had to choose a favorite paleoartist who’s really stood the test of my changing preferences, it would be Douglas Henderson. He is no mere illustrator. His work is truly fine art in the purest sense: stunningly immersive atmosphere, potent composition, mastery of color and light. Bird artists have also become increasingly important to my coterie of influence. Among them are Archibald Thorburn, the principle illustrator of William Beebe’s pheasant monograph; and Jennifer Miller, this year’s duck stamp winner and another master of rich, buttery lighting.

[Paleoart] allows me to fill a niche not anyone could fill. At the same time, I see myself as further on the science end of the spectrum than on the art end. I want to do research, not just illustrate it. I’ve actually had several illustrations completed for publication in my first book, only to later require complete re-dos due to new discoveries about the taxon in question. This is one of the biggest frustrations of being a paleoartist!

That said, I do what I do because paleoart is important. Of all modern scientific disciplines, [paleontology] is the only field where it’s impossible to capture the reality of its natural subjects directly. Like the subjects it studies, the methods of paleontological reconstruction are old: we must paint, sculpt, and draw to bring these animals to life. We are more than illustrators—we are integral to this field’s continued place in the imagination of the public.