“1. Pose a human physiological case; 2. Put in its midst three forces; 3. Lead the characters by logic of their particular being to the denouement; 4. Logic and deduction.”

—Emile Zola

To understand a watch isn’t to watch it but to break it.

Claude Bernard: “We give the name observer to the man who applies methods of investigation to the study of phenomena which he does not vary and which he therefore gathers as nature offers them. We give the name of experimenter to the man who applies methods of investigation so as to make natural phenomena vary, or so as to alter them with some purpose or other, and to make them present themselves in circumstances or conditions in which nature does not show them.”

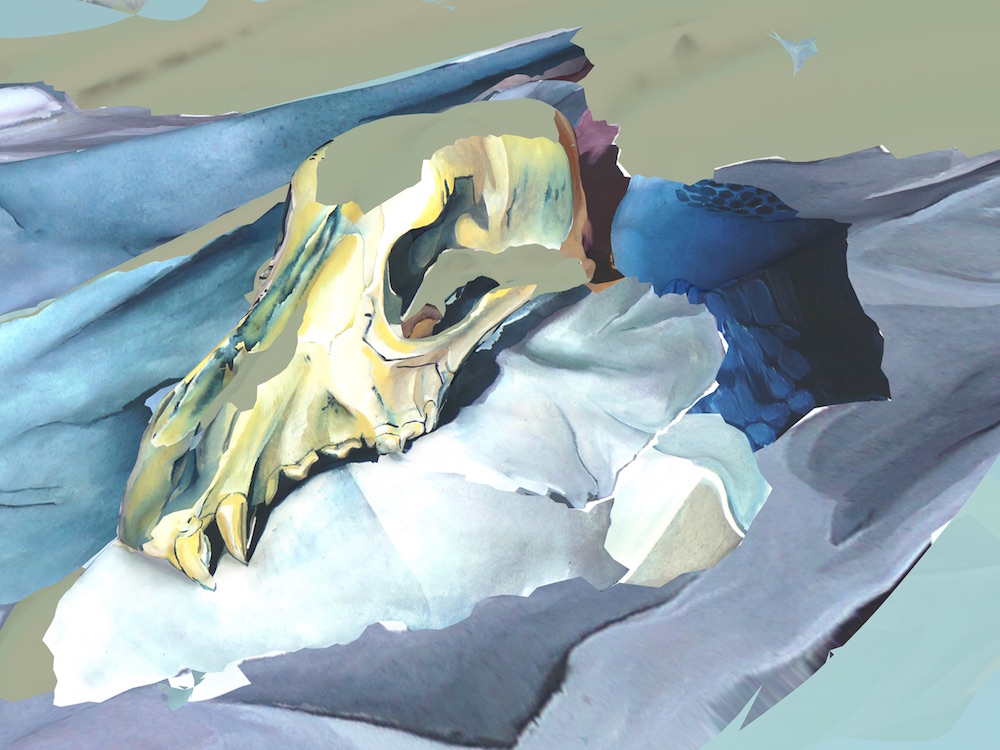

Coolly cutting along the spine of a uncomprehending, screeching dog, “This is our book!” Claude intones, paraphrasing Descartes. A hundred faces balance toward the stage; toward the scientist engrossed in his lesson.

To know the husband’s character, don’t they say look at the wife’s face? Hundreds of faces, come take your look—at this wife stuck in a torrid purgatory, gossips hungry for evidence of my every deed. Why? Because one person’s deed is another’s torment, and that goes for dogs too. “Shush, Fanny,” the grimacers grumble, “why are you always so hot to tell doers from done-tos, or split deeds from each other?” Well, my husband Claude had his deeds, and I had mine, but it’s only my eye where history jabs its finger. A dog is not a book, and neither, by the way, is a wife: our official pages sit blank—dogs’ and wives’—our lives neither exactly forgotten, nor remembered. And don’t tell me how lucky for history that some snoop unrumpled a few of my old letters and lists cleaning out Claude’s desk. A face knows when it’s been made up, and this wife stands smeared with a villainous countenance, and our daughters too. So who wouldn’t parcel out confessions, given half a chance? Listen close. No flies get caught on a burning pot—and she goes safely to trial whose Father is a judge.

“Fanny, didn’t you reach tenderly toward this husband, even once?” Cupid, as the bastard son of Venus and Mars, shoots arrows tipped sometimes with gold, sometimes with lead. The crowd stares expectantly at the wife’s face.

A tiny bichon, a wedding gift from my brother, provides Claude the chance to lecture us all on how a puppy’s personality is retained until death; how a playful dog will wag at you until her last breath. What is pain for, he muses, if not to show who we are? An elevated heart-rate to speed blood to the muscles? Learning not to visit a painful thing twice? I stare, I’m sure, blank of face and understanding. Claude: “One always starts with observation. Then induces.” On the kitchen table, Claude leaves his Red Notebook, in which he jots his laboratory notes and other musings. Maybe he thinks I’m going to be impressed? I certainly read a lot of things. It is later called by his disciples, his “philosophical thesaurus”:

Claude’s Red Notebook:

I have noticed that dogs in which I had exposed the lumbar spinal roots for recurrent sensitivity produced very large quantities of fetid gas. I later noticed, while performing the autopsy, that the cecum was distended by gas, and that the intestinal glands of Peyer were considerably hypertrophied.

Did this relate to the stimulation of the lumbar spinal nerves? Can it be that these glands have a role in the production of gases?

Try to put lead salts in the intestine and see if hydrogen sulfide develops in quantity.

Galvanize and stimulate the nerves to increase this formation of gas, and collect it on the outside if possible.

Instead of sleeping, my new husband spends his nights out of doors, procuring animals for his next day at work: a basket of rabbits, a glass receiver of frogs, two pigeons, an owl, a dog, several tortoises, two cats. I never considered, but all of a sudden I notice, how Paris adores and despises its animals. In every home at least one pet, and courtyards are lousy with cows and hens, shit on stairs and stones. Paris loves animals more than it hates shit-covered stairs, and women would rather walk their dogs than their children. Not to mention shit is good business—sold to tanners by stooped ladies fighting with spoons over the biggest droppings. Meanwhile, the fanciest dog market at Saint-Germain-des-Pres jacks up prices, and ladies strut up and down Pont Neuf with their fluffy prizes. Regulating this surge in pets, a new law requires dogs to be muzzled, and a tax is announced — from one to ten francs depending on the breed. Now people just toss their animals in the river. So the first pound opens, rue de Pontoise, in the shadow of Notre Dame. Dogs are stuffed behind bars, then hanged or struck on the head. “Well bred, good looking” dogs are stored eight days, then sold back to the stalls, while “mongrels, or those without collars or breed,” live without food or water for three days, and are given to people like Claude who show up to take them. As with humans, “class is determined by breeding and partly by occupation.”

Night after night Claude departs into the streets, returning covered in filth, celebrating how the city crawls in animals like meat with flies. Frustrated with Magendie, and now flush with my money, Claude opens his own ‘demonstration theater’ in a cellar at 13, rue Sugar, where to the public, and to me impatiently when I inquire, he trumpets: “This is science as it will become!” Sometimes he ‘starts’ an animal at a friend’s on rue Dauphine, and then leads the audience to rue Sugar to finish the lesson. To curious ladies and gentlemen, as well as to artists and other students, Claude performs these physiology experiments, even if they are only staged facts. One popular ‘experiment’ is on the fifth pair of nerves (the ones for the face) stimulated by mechanical and electrical means. Claude might say: “The scientific principle of vivisection is easy to grasp. It is always a question of separating or altering parts of the living machine, so as to study them and thus to decide how they function and for what.” The audience crowded into his basement sees live rabbits and dogs undergoing this puppet show. A second act might be to damage the brain of a pigeon or cat so it turns only around and around, no longer able to walk straight; more of a comedy, on days that need brightening. Claude laughingly calls himself “the physiologist in the theater.”

Claude’s Red Notebook:

Cut off the ear in newborn rabbits; extirpate it. Then have them reproduce and again extirpate the same ear in order to see if it can finally be caused to disappear (theory of multiple germs.)

For writing up the results of these ‘medical experiments’, Magendie invents a three-paragraph form: hypothesis, action, conclusion. These paragraphs never mention failures or repetitions, and Claude borrows this shorthand, too, for in his scrawled notes one often forgets there’s any animal involved: The lung did such, the vagus nerve such. “Why think,” Magendie shouts from the stage, “when you can experiment? Exhaust experiment, and then think. When I experiment I have only eyes and ears; I have no brain.” Claude also learns the primacy of the choice of experimental animal, which is, he later writes, even more important than tool technique: “The precision of the dog and not that of the instrument.”

Claude proudly reports he’s discovered the trick of cutting dogs’ vocal cords at the beginning, saving himself a lot of trouble. Albert Leffington later confirms: “Bernard was the first to succeed in following the spinal accessory nerve back to the jugular foramen, seizing it with forceps and drawing it out by the roots.” If the aim is silence, or to make the world shut up around him, I have no doubt Claude will build his laboratory behind ten-foot walls, never to be disturbed again. When he’s out at night, I squint at his black or blue handwriting. The words practically dare me to read on, even as I wish I couldn’t. Baudelaire, “The imagination is the most scientific of the faculties.”

Into our home: more filth, more arguments, more mutilated animals, and a new little baby, Marie-Louise-Alphonsine, we call her Marie-Claude. I will repay, saith the Lord. Who was it said that every great tragedy takes place in 24 hours — and in one room, if possible? Claude: “Our existence doesn’t take place in air any more than a fish lives in water or a worm in the sand. The atmosphere, the water, the earth are certainly environments where animals move, but the cosmic environment doesn’t contact or immediately affect the elements of our daily lives. The truth is that we live in our blood, in our internal environment.” Thus the milieu interieur, which Claude boasts he’s ‘discovered.’

It seems Pelouze handed Claude not just a wife, but also poison-tipped arrows from South America. Oorali, wurari, curare comes from lianas trees, the bark boiled to a tar. Claude collects the jars, and explorers’ stories – beginning with Sir Walter Raleigh – and the arrows of hardwood tipped with reeds and fastened with waxed cotton. Into a hole, a poisoned piece of wood is placed.

Claude’s Red Notebook:

“When the brain of a frog is removed, it becomes much more difficult to poison with curare. Why?”

After hundreds of experiments in which animals become paralyzed and yet continue to live, Claude realizes that curare acts neither on the brain, nor the motor nerves, but on their connection. “With curare, no agony, life seems extinguished, but” — Claude leans across the table — “this is not to be! Appearances deceive! This death, which seems so free of pain, is actually accompanied by sufferings more atrocious than the imagination can invent. The victim is not deprived of sensation or intelligence, but only of the means of expressing these through movement.”

Maybe these apple-like fruits were what poisoned the insubordinate Eve, her jaw slackening without a scream. “Curare offers the chance to enter this living machine, this theater of detrimental actions that we will define for you, and explain.” The heart still beating; the blood still turns red in the air. Of course the animal feels every poke and jolt without a way to cry. Claude: “What morality says we can’t do to those like us, science authorizes us to do to the animals.”

After Claude goes out one warm November night, I dare follow in my nightgown, and catch him stalking a pile of palettes near the corner, massed of grey but in the progress of ruin. I fumble, fall out of the doorway while trying to get a good look, and a pair of dogs disappear with a graceful leap. Claude curses for my being outside. Any normal doctor’s wife would be outlining the next day’s meals, listening to children read while embroidering, getting the servants for evening prayers, welcoming seamstresses, making lists of accounts, and hosting lavish entertainments. In other words, Fanny, a good wife wouldn’t look at her husband the way you do, or inquire about his doings. A good wife hears without listening, or listens without hearing, anyway, she is as deaf as anyone who wants to sleep.”

Claude’s Red Notebook:

“Sew the two ears of a rabbit together, then having fused them, cut one below in order to watch the reestablishment of sensibility, and see if the action of the sympathetic might then pass from one ear to another.”

But all my money goes out with Claude and doesn’t return, while the wife of the poor scientist is asked to live in a perpetual spiritual connection to his sacrifices. Everything he talks about is livers and kidneys, blood and nerves, and there is no pew at the Church in my name, so I think about nerves and livers. I look Claude straight in the eye and then slowly return to our apartment. Yet for this mouthful of fire, martyrs soak their words in humble brine. From here, though, I scan the embers as they strive toward flame, and resist the snickering— for all of us locked in this situation forever, slack as marionettes dropped in a box. “Kids should not be cooked in their mother’s milk.” Yes, but, “Do not yoke together the ox and the ass” — right?

In the bookstalls, amid the mayhem, literary ‘physiologies’ are advertised to describe ‘things as they are,’ meaning: ‘very ugly, without softening or embellishing.’ It’s popular now to follow Feydeau and call stories ‘studies,’ with their fleshly passions and violent subjects, dragging all that once was hidden off-stage, the obscene, now front and center. “The ideal is lacking in the naturalist,” says Hippolyte Taine—who studied at the Medical School and is fast becoming the Great Philosopher of the Realist movement— “he is as eager to dissect a door keeper as a minister of state.” Monseigneur says that a wretched fate can be unmade by gaining a wider view, a longer perspective, an infinity in a moment which conquers tragedy through God’s eyes. But the moment one is in pain, the soul cleaves to its mortal body and nothing else, and the mind struggles, unable to free itself to look even a few feet around. Up and still awake, it doesn’t take me long to stand at the window and track where Claude goes. About Balzac, Taine writes: “With such a litter of tools and variety of repulsive preparations that when he emerges from his cellar and comes back to the light, he retains the smell of the laboratory in which he has been buried. He is armed with brutality and calculation; his roughness frees him from fear of shocking people. In this capacity he copies the real, he likes the monstrous on a large scale; he depicts baseness and force better than other things.”

I can’t tell if it’s for the sake of the animals, or for the reputation of Paris, but after so many complaints, the city announces the Grammont Law against abuse of domestic animals — though it doesn’t address vivisection, and pertains only to abuses witnessed in the streets.

Tonight the open window reveals a city alive with noise, as Claude goes out to make his quota. I don’t know what mechanism or force upends my paralysis, but I rise and dress, stomp down behind my husband, and there in the courtyard I meet his eye, just as his boys are handing a pile of puppies back and forth. Ensues between us a new species of ferocious moment. I am unbound like a fury, all hands grabbing and kicking at knees: I refuse to allow even one puppy out of my arms, though they’re struggling and upside-down. I’m screaming bloody murder until Claude nods to one man and they depart into the night. I take the pups upstairs and pack them safely. I go to the church parish where I know the woman who cleans, and I hand them to her, with a promise to help find them homes the next day.

Denis Diderot:

“Woman carries within her an organ subject to terrible spasms; it dominates her, and arouses fierce phantasms of all kinds in her imagination…”

By the next week, he’s yelling that he’s been forced to forgo his Commerce St-Andre-des-Arts laboratory when even the sympathetic commissioner can’t stem the anti-vivisection tide of protest erupting outside the door when he enters and leaves. The flood of noise complaints, and the construction which has everyone on edge, has left the local commissioner no choice but to confront Claude. Now he arrives later and later, only to sleep. The writer, Jules Michelet, describes a dinner table at which wife and daughter attack or refute the husband’s every utterance: “They are on one side of the table, you on the other, and alone.”

Claude’s Red Notebook:

“The experiment is always the termination of a process of reasoning, whose premises are observation. Example: if the face has movement, what is the nerve? I suppose it is the facial; I cut it. I cut others, leaving the facial intact – the control experiment.”

Claude continues hosting his mangled animals in our home, to observe without getting out of bed. The moment he lies down I am awake, hearing his breathing as it slows into snoring. I hate his sleep. The girls and I increasingly share these rooms with post-operative creatures, sitting all night at the dining table giving drops of water, swabbing blood and pus. Claude is trying to keep the animals alive for another day’s lesson; we are gladdest for them to die if they can. In his notes, the girls and I read about frogs fastened into holes leading to dogs’ stomachs, then digested alive, while their desperate attempts to escape are carefully recorded. There is nothing to explain how a fragile peace becomes a violent conflict overnight, but it does. Thanks to Church teachings, I know we should arm ourselves not for quick skirmishes, but for a long war, to battle the inferno we will be forced to face, the resounding wall of madness. Ill, something calls for attention, begs to stand off and accept care, the poor little things who cannot stop their confused pleading until we achieve a small comfort. Going along with this, we succour illness. But refusing to give up the whole for the cries of the little parts, we say, “Part, come back.” Returned to health, the afflicted part loses its partness and fades quietly back.

Charles de Remusat, in Revue des Deux Mondes:

“To raise a hand involves all sorts of actions one must explain, not to leave anything in the dark, the reason which leads, the will which decides, transmission of the will which contracts the muscles. We can separate physical from mental phenomena, explaining some with physiology and leaving reason and thought for philosophy. We’re going to look at the successor of Mr Magendie, Claude Bernard, and his work on the nervous system…”

Claude lectures and demonstrates to his audience how ablation and poisons are the best tools for exploring the mess of live bodies. Once you slice the deceptively smooth skin, everything you think you know vanishes, and the hand must lead where eyes would be useless.

Even for a character hidden away in the crowd, an action sneaks up, a deed, more than just an idea. Maybe this is how you always felt, little girl with courage, but I stayed a pretty good coward until one night I found myself stepping into the street with an extra end of rope, dressed to move faster because a slice of fat to fold into a handkerchief makes all the difference to the nose of an animal. What about the girls sleeping upstairs? What about my own dog, jealous and excited by the fat and the rope? What about the duty to stay at home and guard the house, sleep in it, to sleep at all times as its caretaker? Which was the first dog I caught, and how did I manage it? Was it a little one, lost and alone, rather than already mixed up in a pack as some quickly get? Was it friendly and immediately smelled on my hands the treat it gets for wagging and jumping around my knees while I’m fumbling to tie the right sort of knot? Too loose, and the whole rope slides right out as the dog bows backward and pulls away. Maybe this happened a few times, and the little thing got its reward and escaped. Finally, there must have been the first dog I triumphantly led into the courtyard and up the stairs. I must have bathed and toweled it, locking it into the girls’ room with a dish of water.

Balzac, The Theory of the Bed:

“The hand is essentially an instrument of touch. Now touch is a sense that, in a case when it has to take the place of other senses, gives the fewest wrong impressions; no other sense can take its place…Jesus Christ performed all his miracles by means of his hands. It is through the pores of the hands that life itself passes; and, on whatsoever they touch, the hands leave the mark of a magic power. Again the hand has a share in all the delights of love. It reveals to the doctor the mysteries of our bodies. From it, more than from any other part of the body, exude the nervous fluids, or rather that unknown substance which, for lack of a better term, we must call ‘will.’…A man may be saved by the stretching out of a hand. It serves as the gauge of the various conditions of our feelings…To be accused of want of tact is to be condemned irretrievably. We speak of the ‘hand of justice’, ‘the hand of God’, and again of a ‘coup de main’ when we would describe some brave deed.”

An intimacy more powerful than any intimate act has started to connect my husband and I. My dog-snatching of Claude’s stolen dogs drives him into rages, and even though our network of safety might seem to a stray as just another form of prison, I persist in the slipping of ropes and the binding of jaws, the calming and holding and transporting across bridges, to dim courtyards on the way to other courtyards, the loading into carriages bound for secret places and handed to hands roughly. But my plan, fervent and steadily enacted, has for its counterpart the clueless boys who fear his wrath at their inability to outwit the black-clad lady.

It is asked — after Balzac — what can the new generation of realists do? Balzac announced he would write the ‘natural history of man’; the new authors can go into the senses and the physiological causes that determine them, like Madame Bovary’s “animal awakening,” where “we can feel [her] quivering and shuddering under Flaubert’s pen.”

Gustave Flaubert:

“It is time to give it [art] the precision of the physical sciences, by means of a pitiless method.” Flaubert writes to George Sand, “I expressed myself badly when I told you that one should not write with one’s heart. I meant to say one should not put one’s personality on stage. I believe that great art is scientific and impersonal. One should, by an effort of the spirit, transport oneself into the characters, not draw them to oneself. That, at any rate, is the method.”

A friend who shares his passion for science and the positivists gives the young Emile Zola a copy of Claude’s Introduction to the Study of Experimental Medicine. Zola: “It was necessary to start with the determinism of inert bodies in order to arrive at the determinism of living bodies; and since scientists like Claude Bernard now show that fixed laws govern the human body, we can assert without fear of mistake that the day will come when the laws of thought and the passions will be formulated in turn. One and the same determinism must govern the stone in the road and the brain of man…From that point on science will therefore enter into the domain of us novelists….”

To be sure, not everyone’s so smitten with all this science. Not everyone wants to change what novels are talking about, or expose what imagination hides, tearing apart nerves and brains, and probing why we act or what we’ll do. Baudelaire: “In spite of his admiration for the fiery phenomena of life, never will Eugene Delacroix be confounded among the herd of vulgar artists and scribblers whose myopic intelligence takes shelter behind the vague and obscure word ‘realism’…Those who have no imagination just copy the dictionary. The result is a great vice, the vice of banality, to which those painters are particularly prone whose specialty brings them closer to what is called inanimate nature— landscape painters, for example, who generally consider it a triumph if they can contrive not to show their personalities. By dint of contemplating and copying, they forget to feel and think.”

Saint-Beuve, of Madame Bovary: “Anatomists and physiologists, I see you everywhere!”

Zola: “I call naturalism a return to nature, the scientific movement of the century.”

Claude: “An experiment is performed either to induce a new fact to manifest itself (to see what happens) or to verify an induction or hypothesis.”

Zola: “Is experimentation possible in literature, where heretofore observation alone seems to have been used?”

Claude: “In the conduct of their lives men do nothing but make experiments on one another.”

Zola: “It will be sufficient for me to replace the word ‘doctor’ by the word ‘novelist’ in order to make my thought clear and to bring to it the rigor of scientific truth.”

Claude: “Science works by substituting reason and experiment for feeling, and by showing us clearly the limits of our present knowledge. But by a marvelous compensation, in the measure that science thus reduces our pride she increases our power.”

Zola: “Since medicine is becoming a science, why should not literature itself become a science, thanks to the experimental method?” He will look into social ills and bring their facts into the open. “The problem is to know what a certain passion, acting in a certain environment, and in certain circumstances will produce as regards the individual and society. And the way to solve it is to take the facts in nature, then to study their mechanism by bringing to bear upon them the modifications of circumstances and environment. Just as Mr. Claude Bernard transferred the experimental method from chemistry to medicine, so I transfer it from medicine to the drama and the novel.”

Claude Bernard: “The experimenter is the examining magistrate of nature.”

Zola: “We novelists are the examining magistrates of men and their passions.”

Later, a critic attacks: “Almost too easily, he continues to hide his literary insanity under the cover of a science to which he claims, shamelessly, to be the most zealous servant.”

Zola: “One day physiology will no doubt explain the mechanism of thought and passions; we shall know how the individual machine of a man works, how he thinks…”

As public awareness of our nightly business grows, Tony, Marie-Claude, and I steel against hostile students griping about their professor’s domestic torment. Claude tells everyone I have “made his home a living hell”—as all the while he “keeps the doors of his laboratory closed against the winds of doctrine”—where doctrine is his word for faith. Balzac, from Pinpricks of Married Life: “Civil War. Never was war waged of a more truly domestic nature…two contrary, hostile interests is an exact definition of marriage…for three-quarters of the French people.”