Claire L. Evans is an artist, musician, science writer, science fiction critic, and editor. We spoke about the past, present, and future of science fiction. The following is an edited transcript of our conversation.

Christina Agapakis: How would you describe your relationship to science fiction?

Claire Evans: I’m at best an aficionado. I mean the problem with science fiction is that there’s no real brick and mortar institution in which one can become an expert in this thing—it’s really a self-taught domain. There’s so many different neighborhoods and categories and generations and attitudes. I feel very out of step with most of the science fiction community in 2015 for sure, and it’s rare that I find people who are interested in the exact same kind of science fiction as me.

CA: Which sub-category of science fiction would you call your home?

CE: Let me give you a brief narrative of the history of science fiction, and I’ll drop pins where I’m interested. There are many different starting points, but I think the general consensus is like, scientific romance in the Victorian Age and Mary Shelley—that’s kind of the ballpark. But it didn’t really come into its own as a popular genre—something that had its own demographic and readership—until the 1940s and 50s, the golden age of pulp publishing. Popular mechanics magazines encouraged a sort of rigorous, engineer-driven hard science fiction that appealed to boys. It was 95% space operas and fantastic yarns about spacemen traveling to far-flung planets and rescuing damsels from the arms of slimy monsters and stuff. It’s your John Carter and your Edgar Rice Burroughs stuff.

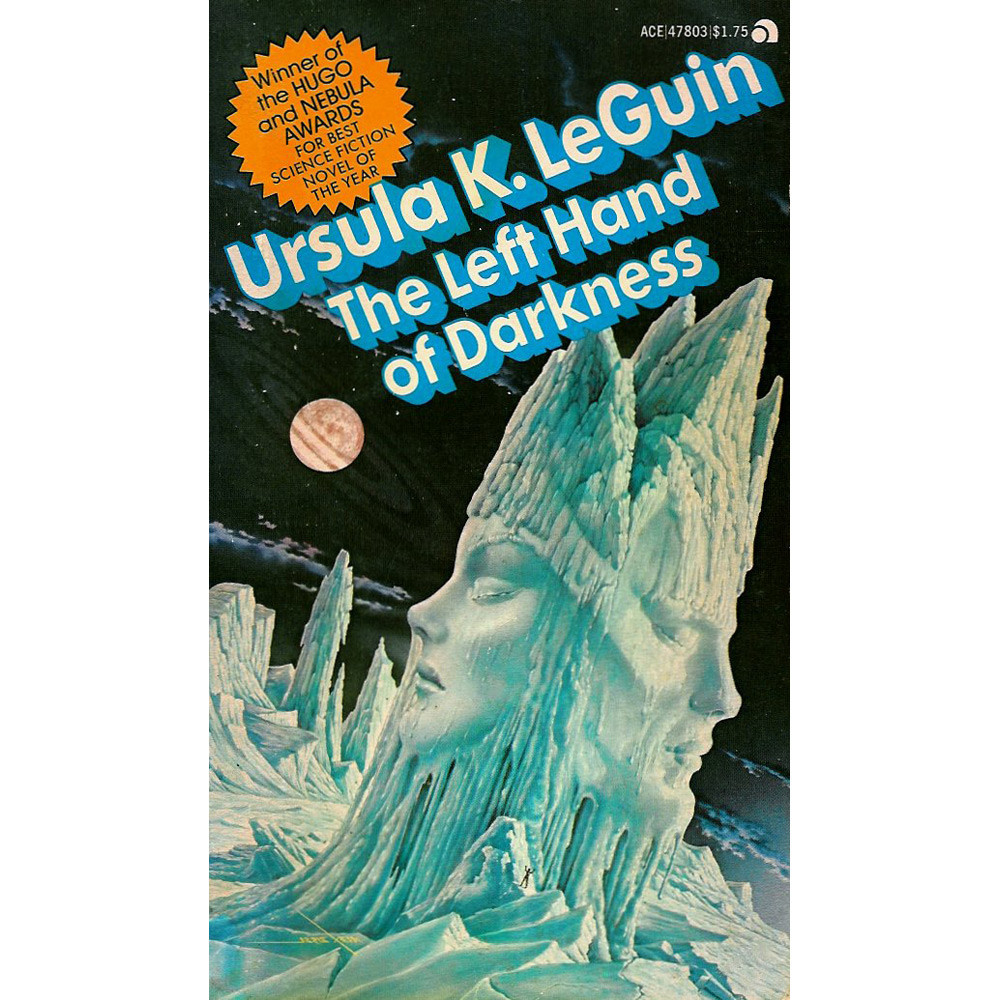

And then, after that, the 60s happened to everything—science fiction too. It bred an era which I think is very interesting, which is called New Wave science fiction, which is sort of the first time that writers that were non-technical people started becoming interested in the genre as a place where people could world-build outside of the constraints of present day realities and kind of internalize all of the lessons of the counterculture movement and start exploring inner space as opposed to outerspace. That was a huge category that included everyone from Ursula LeGuin to Fritz Leiber and Samuel Delany and Philip K Dick and JG Ballard, some people say.

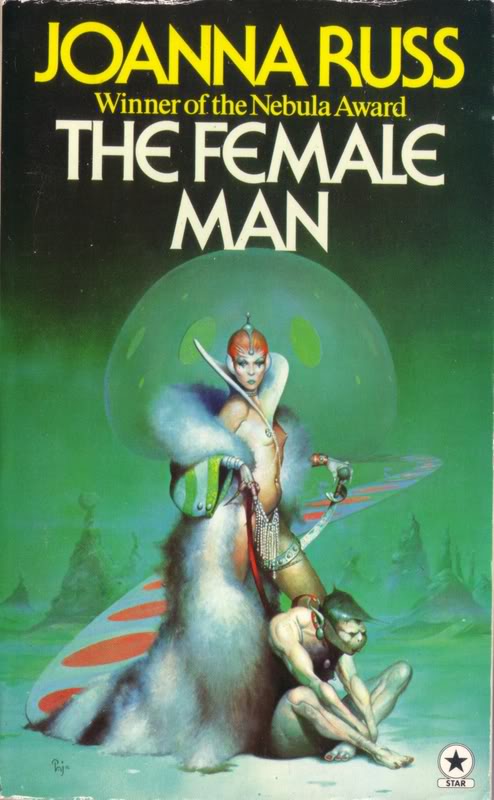

Then in the 70s there was a great and very interesting period of time when feminists started discovering and using science fiction to imagine female worlds and worlds with different social orders. Writers like Joanna Russ, Ursula LeGuin again, a big heavy-hitter. A lot of fantastic work in that period.

The way I’m outlining this now I realize that so far, I like everything. There’s no real low point at which I’ve stopped.

In the 80s and 90s of course there was cyberpunk, which is super interesting as well for its own set of reasons. From the early 60s to the late 90s is my kind of science fiction that I really like, because I feel like that’s the period of time between science fiction’s origins and science fiction’s mainstream-ification that has really happened in the last ten years.

It’s not a countercultural thing to be into science fiction in 2015. It’s either a) a total awareness of the fact that our world has just become a science fiction world, with a million simultaneous futures happening all around us, and b) it’s just part of the commercial enterprise of comic books, television, films. Basically every big blockbuster movie is either a superhero movie or a science fiction movie. Comic Con is a huge corporate-controlled behemoth.

So I feel like it doesn’t really attract the same kind of people that it did in its golden years. Although there are plenty of weirdos still, but as a culture it’s very different from what it was, before I ever had the chance to take part in it.

CA: It is interesting to think about a genre that’s interested in the future, but that you can still romanticize its past.

CE: I think you nailed something, and it’s something I never really realized, which is that a lot of what I find interesting about science fiction of course is the way in which it reflects the present conditions of the time in which it was written. So, the 1960s and 70s and 80s are an interesting period in Western history, and the science fiction of that time speaks not only to what was going on, but what people’s aspirations were, and what people’s fears were. That’s what science fiction does: it presents concise, synthesized extrapolation of the present’s fears, anxieties, and hopes.

CA: Is there a concise definition of science fiction? It sounds like that actually is a pretty good one.

CE: It’s a very difficult to do! In fact, right now we’re in the middle of this very upsetting, Gamergate-style moment within science fiction as a community that is essentially based on conflicting definitions of what science fiction is. There are a lot of people in the science fiction community who think science fiction should be what it was in the 1950s, which was kind of just adventure tales! And escapism!

That’s the opposite of what science fiction means to me. To me, science fiction is a critical tool to understand our relationship to the future. That would be my definition. But those two definitions could coexist, in the same way that a bunch of different types of science fiction can exist, and different audiences. But people are constantly arguing about that. Where you draw the parameters between science fiction and fantasy for example is a big subject of debate in literary academia because it’s a really difficult line to draw. You let one thing in, and then you’re like oh well we’ve got to let this in too.

For me, the line between those two is a sense of the fact that the story at hand exists in a world whose physics are in some way connected to our world. If you create a world and you call it another planet, and you put dragons on it and divine a complete invention where the physics are totally unconnected to our reality—and by physics I mean emotional, cultural, and social physics, just like the dynamics of a world—if all of that is completely detached from our reality, then there’s no point of reference, no way to read the story as a criticism or an extrapolation or as a version of our world, which to me defeats the purpose. Even if the connection is really tenuous, there needs to be some kind of line, some kind of tether connecting our world to the world of the story. And if that tether is “1000 years in the future” it doesn’t matter—as long as there’s something so you can say if we behave in a certain way, then our world could become this world. Or, this is a picture of what a world like ours with this one variable change would look like. That’s the pivot upon which the real critical power of science fiction must exist.

CA: Did your history with science fiction follow a similar path as the history of science fiction? What made you first fall in love with science fiction—was it the adventure story, was it the cyber punk, or was it somewhere in between?

CE: I think there’s a pretty clear analog between the narrative that I just painted for you and my personal journey with science fiction, because science fiction is a genre that came into existence and then grew up within the last 50 years. The books that I read as a little kid and that I loved where books by people like Ray Bradbury and Arthur C. Clarke, who are amazing writers, but who are writing from this place that is largely based on the pragmatic speculation and the desire to convey the wonder of science to the broad public. That’s fabulous.

And then I got into the sort of post-modern science fiction when I was in college, which is when one gets into those kinds of things, and then got into feminist science fiction in the last five years…as I became a woman. And maybe now I’m destined to become a cyberpunk because we live in a sort of hellish urban dystopia. Eventually I’ll catch up with it!

CA: What does it mean to write science fiction as a feminist, and explicitly write feminist science fiction?

CE: Where to begin! It’s interesting because feminist science fiction emerged along with second wave feminism. If you read canonical feminist science fiction books it really is the concerns of second wave feminism being displayed in a particularly fun and funny way. The general attitude of that era of writing was kind of nose-thumbing and subversive and willfully self-aware and pissed off. There’s this wonderful anger and zeal to that fiction that makes it really delightful to read.

I think that there are very few mediums that are as effective as science fiction for exploring the aspirations of feminism, because science fiction is an extremely powerful tool not for predicting the future but for clarifying the present. What really good science fiction does is it takes some fundamental concept—like the way that society is ordered or the conditions that we take for granted as people who are born human women. If we change something about that, we make the conditions slightly different, if we make our biology slightly different or our mode of reproduction slightly different, then all of a sudden it changes the way that society is ordered all around us.

To see that, to imagine what the world looks like with such a tweak, it allows us to understand that our condition is as arbitrary as any of these other variables. All these different imaginations of the world are equally arbitrary. It does a good job of helping us loosen up our ideas of what we should be comfortable with.

Imagining a female-only world—just the idea of it is so speculative and surreal because we don’t experience it in our day-to-day. I know that the times that I’ve found myself in spaces where I was surrounded by only women, there is something that changes about the physics of that space—people talk differently, in a different register, people talk about different things, expectations for intimacy and meeting new people changes, levels of trust, hierarchies are different. To imagine that extrapolated into a state of normalcy at all times is profoundly compelling because it’s something we never experience in our own world.

CA: Are there contemporary writers that you think are making feminist science fiction? Is there a community or anything you can point to besides these writers from the 70s?

CE: For what it’s worth, I don’t know that science fiction writing is the medium for this kind of thought of our time. It worked really well for the 60s and 70s because that was a time when science fiction was being explored by a lot of intellectuals and it was finding a place in discourse that it had never had before.

If you want to convey a powerful idea in 2015 that you want to share with a lot of people, I guarantee you writing a science fiction story about it is definitely not the avenue. There’s not a huge audience for this type of thing! I think that the Joanna Russes and Ursula Le Guins of today are Anita Sarkeesian and women coders and hackers and people who are doing the same thing of entering boys’ spots. Or that’s what I would hope—that women who are making games, and making software, and working for big tech companies, that that’s where it’s happening. And that’s where you see a lot of the backlash. It’s always where the backlash is that’s where it’s happening. As dark as Gamergate is, I think it’s an indicator that new agents are entering these traditionally male spaces and doing interesting stuff within them.

CA: How do you think that science fiction in any of its forms affects the practice of science and technology? How does it sort of trickle back into the ways we do technology?

CE: I think that a lot is made of the fact that science fiction writers every once in a while throughout history—banging at a typewriter—got something right. People always say that Arthur C. Clarke invented the communication satellite. And yeah, he did, kind of. But that’s one instance in untold thousands and perhaps millions of stories and imaginations that didn’t turn out to be the truth. And so obviously I don’t think that science fiction’s role is to be predictive when it comes to technology, and in fact I think that’s a reductive way of reading it. No artist should be held accountable for whether their imagination came true! That’s not the point of imagination.

But I do think that what science fiction does really well is that it imagines technologies—whether or not those technologies come true is irrelevant—and then it spends a great deal more time imagining how those technologies will affect the world, and affect how people deal with one another in larger social groups. And reading those social imaginations about how technologies change people, allow us to sort of prepare ourselves for the possible contingencies of the future.

I always say that science fiction softens the edge of the future. It acclimates us to new possibilities and to new potential social orders and new environments. That allows us to begin to internalize the possibilities of the future, then as we move forward into the future we often find ourselves kind of reiterating those imaginations based on some kind of collective mentality about things we were told, the stories we grew up reading.

There’s always been this sort of tangled hierarchy between tech and science fiction, because can you say for sure that we would have landed on the moon if the engineers who made that happen hadn’t grown up reading Arthur C. Clarke? Would we have anonymous hacker vigilantes roaming our world if those people hadn’t read William Gibson and Bruce Sterling and all those people? As much as science fiction doesn’t predict the future it often causes it to a certain extent.

CA: What inspired you in writing Pythia? What aspects of the present and future were you addressing?

CE: A couple of things. I think the story kind of emerges from a personal place of being kind of frightened of the idea of giving birth, frankly. I’ve always been a little bit scared of it as this piece of like body horror.

I also think that female fecundity is so science fiction already! It feels like an alien thing, because it’s something that you don’t consider until it happens to you and then all of a sudden there’s this thing inside you. There’s literally an alien growing inside you, though obviously that’s not how it’s really going to go down.

I was sort of also trying to tap into a little bit of this Philip K. Dick thing, which is sort of the line between individuals. I think it’s miraculous and insane and not often said out loud how bizarre it is that there are billions of us on this planet and no two of us are the same. That is something that’s just phenomenal! You give birth to a new human being and it’s a new face in the world.

But what if it wasn’t? What if instead of that being the case, what if instead of biology just giving us this salad of features that are related to our ancestors every time we give birth, what if it was more of a one-to-one thing where you give birth to yourself, or you give birth to one generation behind you?

There’s also something just about the circles of life. There’s a vulnerability with age. We have this fierce sense of independence during the prime of our lives, but then we become more and more dependent on others as we become older, until we reach the end of life and we are completely dependent on people around us, and totally dependent on these people we created. I was interested in sort of flipping that on its head.

It’s also an intergenerational love story. If you were a child in one generation and are born again as a child, then grew up into the adult version of the person that you once were, and then you meet an artificial intelligence that’s made out of the person you once loved, would you fall in love with them again?

CA: That reminds me of something my husband recently told me about an Inuit culture (he’s an anthropologist) where if you’re named after your grandfather, you refer to everybody as if you actually were your own grandfather—you would call your mother “daughter.”

Which brings up another question—we talked about feminism, but what about culture? Different cultures have different ways of being in the world and imagining the present and foreseeing the future. How has American science fiction engaged with other cultures?

CE: So basically in the science fiction before like the mid 1970s, if there was an alien it was either a Russian, a woman, or a gay. It was totally based on who was writing it! Because the alien, or the “other”, in science fiction is always the other of whoever the writer is. So for a long time it was your traditional “others” in a patriarchy.

But that’s also what’s interesting about feminist science fiction is that a feminist writing science fiction, her other is a completely different set of parameters. Her other is the ethos, her “other” is the patriarchy. There’s actually a great Joanna Russ story called “When It Changed” about a planet in which a colony of human beings has been marooned. 50% of the population, the male half of the population, was wiped out by a gender-specific plague, leaving only the women to continue on. The story takes place 900 years later, after they’ve completely re-figured out their society and figured out some sort of autogenic way of reproducing, and built cities and sophistication.

Their world is quite robust although on the brink of being industrialized, they’ve managed to solve all the main problems. And then a ship lands on their planet of male astronauts who’ve come to rescue them, and no one on this planet has ever seen men before—they’ve only heard about them in stories, because it’s been 30 generations. So there’s a description of the male astronauts written from the point of view of Janet, and it’s interesting, it’s so good.

CA: You wrote about that in your Motherboard piece! I have it here:

They are bigger than we are, they are bigger and broader. They are obviously of our species, but off—indescribably off!

CE: Yeah! And I think it’s only in the last 25-30 years that we’ve seen science fiction written by people from all these other countries—there’s anthologies of French science fiction, African science fiction. I haven’t read nearly as much of that stuff as I wish I had, but as a tool it has the power to really change people’s understanding of what the Other is. And, again, make any other human occupy that.

CA: I wanted to ask you also about your work as an editor and what you’re doing with Terraform. Where you do see a place for that kind of writing in the current online ecosystem?

CE: Terraform is there to publish stories that extrapolate from geeks who are in conversation with the news, the Twitter stories, that are on Motherboard and all the other various Vice channels. So I’m working in concert with journalists to create speculative content based on things that people are talking about in the present. If there’s an interesting drone story happening in the news, then we’ll try to run something on Terraform that speaks to that. We had a story of a dystopian world in which Uber controls all resources. Or we had a reimagination of Coachella as a militarized tent city in the desert.

It’s very difficult to get people to think about fiction as something that should be part of life, part of the discourse about technology, part of the conversation about the future—really just a tool for framing issues. That’s kind of my struggle with Terraform—trying to find ways of publishing fiction that gets people to think that way about it. Speaking to current event stuff seems to work really well and is actually really fun.

We just ran a story this week that’s based on something that’s happening in the science fiction community right now. There’s the Hugo Awards—the big literary awards in science fiction. This year there’s a vulnerability in the ballot system that allowed all members of this group—you can just pay a small fee to join—to vote for the awards. This extremely conservative, sort of Gamergate contingent of people who basically think there is too much diversity in science fiction and want science fiction to go back to what it was basically kind of gamed the ballot system, and now the highest honor literary award in science fiction is stacked with insane, racist, mysoginist fiction. A lot of people have withdrawn their entries. A lot of people aren’t going to the Hugos this year. It’s kind of broken the community from the inside.

We commissioned a story this week from a Hugo-winning woman writer imagining what the world would be like if we let these trolls win. It’s this kind of horrific dystopia where all futures have to be mandated and approved by the patriarchy. Doing stuff like that is fun, because it allows us to use the genre for what it’s good for—which is to be critical—and in a sense that makes us a very political magazine.

But generally speaking, of the hundreds and hundreds of submissions that we get, there probably are four major themes: anxiety about social media, future of warfare, sex (so many android sexpot stories, it’s unbelievable), and then there’s the whole category of stories that are your standard space adventure story—pure escapist stories. It’s really sex, social media, and more. Those are the concerns of our age.

CA: You’re also are a musician—how much does your passion for science fiction play a role in the work that you do as an artist and musician?

CE: I used to think that everything was siloed, that everything was its own thing—that I had different sort of personal projects and that they all had their own identities and had no overlap. And then a couple years ago I decided that that was sort of an untenable way to be a person in the world. At a certain point I knew I’d look back on my life and see, zoomed out, that it was actually just one big thing that whole time. That’s the way I think about it now, and nothing’s really changed in my practice, but my own perception of it has changed.

YACHT, as a band, is pretty tech-centric. It’s an acronym—for Young Americans Challenging High Technology. There are a lot of things that we do that engage with the kinds of questions that I find interesting in science fiction, and I think that a lot of our songwriting has kind of a narrative component. It’s critical of the world in sort of a science fiction-y way—critical of our position in this technological amnion that we live in, somewhat cynical about the future, but in a self-aware kind of way. There’s a lot of ways in which the content sort of plays back and forth.

There’s a lot of ways in which the content sort of plays back and forth. It’s always useful to have lots of different things going on and to be operating on different sides of your brain. I mean I write about science and technology—that doesn’t make me a scientist or a technologist—but at least I’m thinking about those things, and I think it takes a different kind of thinking to think about those things than it takes to do songwriting or a performance. It’s always good to be flexing the whole muscle, and to bring rigor into creativity and to bring looseness into the way that I think about technology.

CA: I don’t think it’s fair to say that rigor belongs only to science and technology, because I know a lot of artists who have a really rigorous practice, but they’re not allowed to think of their stuff as rigorous—because art is “not like that.” And science—which can be so loose; we’re figuring it out as we go along—has this halo of seriousness and rationality, and we’re always doing the right thing at the right time and asking the right questions, when in reality it’s not like that.

CE: The thing that I like about science is that as a discipline it’s something that thinks about itself in a larger context. You stand on the shoulders of those who came before you, and you answer the questions they couldn’t answer, the people that come after you answer the questions that you couldn’t answer, and can fix the things that you got wrong, until finally we reach the end point where we’ve got it all figured out. Obviously that’s a narrative that doesn’t always work, but I don’t think artists really think of themselves in that way.

CA: I think even in science when it comes to traditions and lineage, that it’s not a single line—but a landscape. You have inspiration and influences and people who you influence—you take some methods from some people and some questions from some other people, and then you’re like “oh that’s really interesting,” because there are so many things to think about and to study. And there is no end, just like I think there is no end point to art. Maybe there’s more of an overlap than we might think.

CE: Yeah, it’s really interesting. We define creativity as the capacity to draw elements from all over the place. As an artist, I always think about well I love this band, and I love this movie, and I love this color, and bringing them all together is what I bring to the world. It’s like a percolation of all of these disparate things in the teapot of my brain, and then whatever I create is original perhaps, but also comes from all these different places.

CA: I agree! What do you think the future of science fiction is? If you don’t want to use science fiction to predict the future, do you ever think about the future of science fiction?

CE: I am interested in discovering new forms of manifesting the science fictional gesture. I love writing, I love text, and I love stories, but I also think there are so many new ways of telling stories, and I’m really interested in discovering what those ways are. There’s so much potential in gaming to tell stories in new ways, and I’d love to know who like the Philip K. Dick of videogames is going to be. I want to publish that person, you know?

I don’t know—science fiction will always reflect the needs of its time, and evolve with its time. And so, I think that it’s very difficult to predict what the future of science fiction will be; it’s just as difficult as predicting what the future will be, frankly. It’s there as this mirror on the future, this mirror that exists alongside the future. As we move towards it, it moves away from us in equal measure.